TRG Info and Advice

Rice: the Essence of Japan

Japanese cuisine is, undoubtedly, centered around rice. Cooked rice is called “gohan” or “meshi,” in Japanese, words which also carry the meaning of, simply, a “meal.” For traditional home meals, rice is typically the staple and served along with one or more side dishes (called “okazu”) made from vegetables, meat, or fish, and one soup dish. As rice itself has a neutral taste, it is a versatile base for a myriad of cuisine, from East to West.

Many Japanese people eat in a triangular pattern (called “sankaku-tabe”), alternately taking from each dish: rice, side dish, soup. Eat a bit of rice, eat a bit of the side dish next, then a sip of soup, and repeat this pattern. This way, the tastes of rice and other dishes become mixed in your mouth, and the plain rice is seasoned. Likewise, dishes that might taste too salty or strong by themselves can, with the triangular eating pattern, produce a perfect harmony of flavors.

Nowadays, Japanese people are eating more bread and noodles than before, and health conscious people are choosing not to eat much rice, in order to achieve a low-carb diet. Therefore, household rice consumption is decreasing by approximately 80 thousand tons annually, nationwide. You might think Japanese people are big rice eaters, and that’s not necessarily wrong, but the average per-capita rice consumption is about 160g per day, which is just a little bit more than the world average (148g per day). 150g is the average weight of a bowl of rice, so these days, Japanese people are eating about as much rice as other nations.

Take a Guess!

How many grains of cooked rice do you think there are in a bowl with 150g of rice?

See the bottom of this page for the answer.

A Brief History of Rice Farming

When and where rice cultivation began has been long debated. The most recent research suggests that rice agriculture originated simultaneously in the middle and lower Yangtze district of China, the Ganges plains of India, and western Africa, and spread to the rest of the world from those locations.

Rice cultivation is thought to have been brought to Japan from Mainland China, although the details as to which route the “rice road” actually took are unknown. Archaeological discoveries indicate wet rice farming had already begun around 3,000 years ago, while the cultivation of rice in dry fields may have been in existence even before that.

Rice and Japan

Wet rice cultivation is a labor-intensive task. It involves many steps: growing the rice seedlings, flattening the paddies to make a bed for the seedlings, damming the sides of the paddies with mud dykes to ensure they will hold water, planting, weeding, insect repelling, harvesting, threshing, and so on, almost all of which used to be done completely by manual labor (with the help of cattle) before mechanization. As a result, the everyday life of farmers was centered on the cycle of agriculture, so seasonal timeframes formed, and many events aimed to pray for bumper crops and to give thanks for the year’s harvest also developed. Rice cultivation required harmonized, concerted efforts by many villagers for all of the processes, along with water management and other works such as re-thatching the roof of neighboring houses. Consequently, community groups called “yui” were formed, which became the foundation of Japanese society. Other characteristics of Japanese culture, including the mentality of consensus-seeking and commitment to group harmony, were also enhanced.

As rice cultivation spread throughout the country and rice became a desired staple over other crops, it came to underpin the economic system on a national scale. Since ancient times, rice was traded as currency, and even taxes were paid with rice until the early Meiji Period.

As books written in the Heian Period indicate, rice was used in court rituals, as well as, given as a salary and food to courtiers and workers. The year’s first crop of rice was considered the most important, and was used during a ceremony of the Emperor’s (called “Niinamesai”), where he dedicates it to the gods to give thanks and tastes it with reverence.

In the Edo Period, feudal lords collected rice as taxes from farmers, which were was then given as wages and food to service members (samurai), and also exchanged for money to spend on goods. That brought the emergence of large rice storehouses and rice brokers centered in Osaka, where a rice futures market was hosted.

The rice-based tax system ended in the beginning of the Meiji Period, but tenant farmers still had to pay rent to landowners with rice until the Land Reform initiated by the US Occupation.

Rice has been considered sacred and was even used to drive away evil spirits. As such, rice plays a vital role in not only food and economy, but also in tradition and culture.

Rice cultivation is closely linked to nature so, drought, extraordinarily cold weather, typhoons, and other uncontrollable conditions have a huge impact on crops. Many festivals and seasonal ceremonies, such as New Year‘s traditions, are said to be derived from the prayers and thanksgiving for bumper harvests paid to the gods of rice paddies.

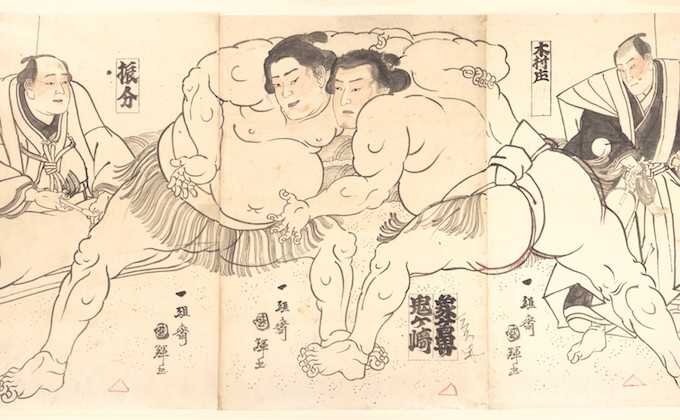

Japanese traditional culture is also deeply associated with rice farming. For example, performing arts such as dengaku are considered to have originally come from music and songs performed during rice planting. Japan’s national sport of sumo was originally a ritual carried out to divine the year’s yield and to pray for bountiful crops. It then became a part of annual events at the imperial court, which is the original form of sumo today.

There are also traditions of dedicating a heaping bowl of rice, or offering rice and salt to gods on special occasions, such as births, weddings, and funerals.

Mochi (rice cakes) and sake (rice wine) are made from rice. Mochi is used as a sacred food where deities gather, and sake serves as a medium to communicate with deities in Shinto rituals and festivals.

Very little of the rice plant goes to waste: not only rice grains for food, but rice straw, rice bran and even the water used to rinse the rice before cooking, were essentials of everyday life. Straw was used to make roofs or to strengthen mud walls. Rugs, bags, slippers, raincoats, boots, ropes and rice sacks were also woven from straw. New Year’s decorations and barrier ropes at Shinto shrines are still made of straw. Rice bran is used to make pickles by mixing it with brine, and also to remove bitterness in bamboo shoots. The milky white water that appears after rinsing rice, and rice bran were used as soap and laundry detergent.

Wet-rice Species

Nearly all wet rice is divided into two sub-species: Oryza sativa indica and O.s. japonica, both of which encompass thousands of varieties.

Indica rice is mainly cultivated in the tropics, whereas japonica rice is grown in temperate areas and has a tolerance for cooler temperatures.

This is why japonica rice is the major species grown in Japan. Among japonica rice, there is another variety called javanica also known as tropical japonica, which is grown in dry fields in the tropics.

Features of Indica Rice

Though most types of indica rice are long and narrow, and remain separated and flaky when cooked, some varieties are roundish and small like Japanese rice.

Indica rice is cultivated mainly in India and Southeast Asia, as well as, in the United States and Australia. To cook it, lightly rinse to remove dust and then boil in plenty of water.

Indica rice best suits pilaf, Indian curry and paella.

Features of Japonica Rice

Japonica rice is short and roundish, and when it is steamed, it becomes sticky and shiny.

Japonica rice is the best choice for sushi and onigiri.

Rice Varieties

Uruchimai (ordinary rice)

Eaten most commonly in Japan, it gets harder when it cools.

Mochimai (glutinous rice)

Mochimai is mostly used to make rice cakes and sekihan (steamed rice with red beans). It remains fluffy and tasty when cooked.

Aromatic Rice

Kaorimai (aromatic rice) is used as a treat for feasts on special occasions like festivals. When 10% is added to ordinary rice, it produces a savory aroma.

Akamai (red rice)

Red rice is considered to be the first variety of rice brought to Japan from China in ancient times. It is high in protein and vitamins. Akamai is said to be the origin of sekihan.

Kuromai (a.k.a. kodaimai: black rice)

One of the rice varieties brought from ancient China, kuromai contains black pigment in its surface. Add a tablespoon to your regular amount of white rice before cooking for a lovely, purplish result.

Midorimai (green rice)

Midorimai is an ancient rice variety brought from China in the Jomon Period. It is cultivated mainly in Nepal and Laos.

Sakamai

Sakamai is the best rice to make sake. As it is polished to a greater extent than ordinary rice, and the size of the grain is important.

Sprouted Brown Rice

With a 0.5mm-1.0mm sprout, germinated brown rice is considered a healthy choice, as it has a high GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) content.

The Development of Rice Varieties

The history of rice is really a history of the development of varieties.

In order to cultivate a greater amount of delicious rice with fewer troubles and less labor, disease-resistant, heat and chill tolerant, and easy-to-grow rice varieties have been repeatedly developed over time.

Variety selection and development came into full swing in 1903, when the improvement of agricultural productivity was one of the most pressing issues to be tackled. In the same year, the foundation of the hybridization method (crossing two fine cultivars) was established in a national agricultural experiment station. The first cultivar developed in this selective breeding method, Rikuu No. 132, began to be cultivated in Akita in 1921. Rikuu 132 was chill-resistant, and widely grown in the Tohoku region. Since then hybridization has been repeated, and over 700 varieties of rice were developed, among which 300 varieties are still cultivated all over Japan today. Variety development is not limited to rice as a staple, but also for those varieties used for sake, rice powder and animal feed.

Koshihikari, a common, delicious rice variety, was born in Niigata Prefecture in 1944. Aiming to develop a delicious and disease-resistant strain (particularly against blast, the most serious disease at the time), Koshihikari was developed by crossing Norin No. 1, which has great quality and flavor, and Norin No. 22, which has high disease resistance.

Although Koshihikari has thin stalks and tends to fall over easily, it came to be cultivated wider and wider because of its high quality and deliciousness. Koshihikari is now being grown nationwide, except in Hokkaido and some parts of the Tohoku region.

Japanese Rice Varieties (wet-field ordinary rice)

*The figure indicates overall Japanese acreage percentage in 2016.

Koshihikari: 36.2%

The most popular Japan-produced rice, Koshihikari is valued most highly in the areas of flavor and stickinesss.

Hitomebore: 9.6%

A rice variety developed in Miyagi Prefecture, Hitomebore has a good balance of stickiness, gleam, flavor, sweetness and aroma.

Hinohikari: 9.1%

A representative rice in the Kyushu region, Hinohikari is less expensive than Koshihikari, with a similar flavor and gleam.

Akitakomachi: 7.0%

A rice variety developed in Akita Prefecture, it remains delicious even when it gets cold, so it suits bento (boxed meals) and onigiri.

Nanatsuboshi: 3.5%

A rice variety developed in Hokkaido Prefecture, its features are the perfect level of sweetness and stickiness, and a light flavor.

A Rice Farmer’s Perspective: The Hundred Jobs of a Hyakusho

(Hyakusho is an old-fashioned term for farmer/peasant, literally means: one hundred surnames)

With an aging population, and a postwar increase in flour-based staples that has led to the amount of rice consumed in Japan to be halved, plus looming international policies like the Trans Pacific Pact, many farmers are concerned with the future of their fields. Government practices like “gentan,”where farmers are forced to cut or burn extra fields of rice before the harvest in order to avoid a surplus and maintain a competitive purchase price, have farmers wondering if the people making these policies actually understand what goes into getting a grain of rice to the point where it can be consumed!

Programs to entice the younger generation are being put into place, with monthly stipends for working with experienced farmers, in exchange for the promise to continue farming for a certain number of years. Cooperatives, too, forming between like-minded groups to grow organic, or reduced-pesticide rice, beans or other grains, or to share machinery, provide a ray of hope, but much more is needed! Small, irregular shaped paddies may be a national treasure, but are unrealistic for one aging farmer trying to do everything alone. Larger paddies need larger tractors, planters and combines. Postharvest machinery such as dryers and huskers are expensive and often in need of repair. Local government’s ridiculously low purchase price is forcing some farmers to sell privately, which involves advertising, packaging and other secretarial tasks that have to be performed along with the million things involved in growing rice. Consumer demands for perfection have led to the purchase of outrageously expensive “color selection” machines that weed out any grain of rice that doesn’t look exactly right.

Crop rotation and diversification are viable options for farmers with plenty of land, but often require special machinery in the production process. Heirloom rice varieties are becoming more common as they are both interesting and healthy; but finding a market for these alternative crops is often more work than its worth.

Creative problem solvers are doing what they can, though. One farmer rescued his selection machine’s still-delicious and safe rejects, and marketed them as “kotsubumai” (miniature-grain rice) at a reduced price. “Tanbo Art,” where rice is planted or cut in a way that creates a recognizable picture (like the one celebrating Sado Island’s Ten-year Toki Anniversary), was a popular tourist attraction this summer. Students from Tokyo’s Agriculture University are invited into the countryside for hands-on experience, providing much-needed free labor! Those with gluten allergies are pressuring bakers to make bread and sweets using 100% rice flour. These actions show that there is still some fight left in the farmers, and cultural safe-guards, of Japan!

How to Cook Japanese Rice Perfectly

A rice cooker can cook rice perfectly without any trouble if you follow a few steps.

Even without a rice cooker, you can cook perfect rice using a pot with a tight fitting lid such as a donabe (earthen pot).

1. Rice condition

It is best to cook rice right after milling brown rice. When you choose rice to buy in a shop, choose the one milled most recently.

<<Milling levels>>

Brown rice: rice with a germ and an outer husk

Haigamai: Haigamai is rice half-milled to remove the entire husk and 20% of the germ.

Hakumai (white rice): Rice without the husk or germ

2. Weigh or measure the rice carefully.

The basic ratio of rice and water is 1:1.2. This ratio changes depending on the type of rice being cooked. For brown rice, the ratio is 1:1.5 and for haigamai it’s somewhere in-between.

3. Rinsing rice

Rinse the rice well with water quickly so the rice does not absorb the smell of rice bran.

①Place rice in a bowl and pour plenty of water over it quickly. Swish the rice around from the bottom once, and drain the milky white water away immediately (or save it to use in your bath or as a facial toner if the rice you are washing is organic).

②Add a little fresh water, just enough to cover the rice. With your fingers, scoop the grains from the bottom and, using the heel of your palm, press down gently but firmly, rubbing the grains against each other. Repeat this step a couple of times, turning the bowl with your other hand so that you are not always scooping from the same place. Then, drain the cloudy water away. Repeat this step until the water becomes almost clear.

③Drain the rice in a fine mesh colander.

4. Measuring water

Pour water over the rice. Newly harvested rice contains more moisture than older rice, so reduce the amount of water slightly, while older rice contains less water, so cook the rice with a little extra water. You can, however, adjust the amount of water according to your taste, and for what you are planning to make: fried rice, sushi rice, etc. When cooking Japanese rice, use soft water, not hard water, which does not permeate rice grains sufficiently.

5. Water absorbing time

Once sufficient water is added, leave it to soak for about 30 minutes in summer and about 2 hours in winter, so the rice grains can have enough time to absorb water. This time also varies according to the type of rice being cooked: for brown rice, let soak overnight in winter and for 2-3 hours in summer.

6. Cooking

Basically, all you need to do is bring the rice to a boil, then turn off the gas or burner. A rice cooker, which can automatically adjust the heating and resting time, is the easiest way to cook rice, but you can still make rice in a regular pot. When you cook rice with a pot or saucepan, make sure you have a tight fitting lid with a hole. Bring it to a boil, and keep your eye on the amount of steam coming out from the hole in the lid. Once the steam begins coming out vigorously, remove the pot from the heat. Don’t open the lid yet! Leave the pot to rest for about 15 minutes. This step can make rice grains absorb water evenly.

7. Turning over / Keeping cooked rice

After the resting time is over, remove the lid and stir the rice by gently turning it over, scooping from the outside in, using a rice paddle. Then let it rest a little more. This final step can make a huge difference and allows excess moisture to evaporate. Do not leave rice in the rice cooker for a long time, because if you do, moisture keeps on evaporating, and the taste becomes less delicious as the color and aroma change. If you cannot consume it right away, there are various ways to preserve the flavor of freshly-cooked rice. The old-fashioned way, or eco-friendly option, is to place a dampened steaming towel in a round wooden container with a lid, called an “ohitsu.” Fill the towel with rice and wrap it snugly, then replace the lid. The ohitsu keeps the rice moist and fresh, and even when the temperature drops, the flavor remains delicious. In these modern times, there are other options as well. Some people have an electric heating “jar” which keeps the rice hot. Others wrap leftover rice while it is hot in plastic film and keep it in the freezer. When you want to eat it, just warm it up using a microwave and you can enjoy a flavor similar to that of the freshly cooked rice.

Rice Dishes and Rice Products

Sushi

Usually when people say “sushi” (a word that combines the Japanese word for vinegar, “su,” with the Japanese word for rice, “meshi,” and actually refers to vinegared rice) they are talking about vinegared rice combined with other ingredients, most typically, fresh seafood. You can enjoy sushi (vinegared rice) in a variety of ways: hand-crafted, small pieces with fresh seafood toppings (nigirizushi), covered with scattered toppings of seafood and other items (chirashizushi), rolled with fillings in a nori sheet (makizushi: sushi rolls) or stuffed in seasoned, deep-fried tofu bags (inarizushi).

Onigiri (rice balls)

Onigiri is made by filling rice in various shapes (such as triangles and rice bags) and a variety of sizes, with ingredients that range from sweet and salty seaweed to grilled tuna with wasabi mayo. Onigiri are often served with a belt or wrap of nori, and usually taste good even if they get cold. Recently, sandwich-like “onigirazu” have become popular.

Kayu (rice porridge)

Kayu is watery, cooked rice made by boiling it in plenty of water. There is also “chagayu,” which is made by boiling rice in roasted green tea, instead of water. Kayu, which requires little chewing, can be used as the perfect baby food, a nourishing meal for people recovering from illness, or a gentle menu item for the elderly.

Zosui (rice soup)

Zosui, also called ojiya, is rice soup made with a variety of ingredients, such as eggs, vegetables, seafood, and others. Zosui is often enjoyed as a finish for a hot pot meal, using the leftover soup.

Okowa

Okowa is glutinous rice (mochimai) steamed in a steamer basket. There are several varieties of okowa, from sekihan with red beans, and kuriokowa with chestnuts, to sansai okowa with edible wild plants.

Donburi

Donburi is rice in a bigger bowl, with the side dishes served on top, and includes gyu-don (beef over rice), oyako-don (chicken and egg over rice), katsu-don (breaded pork cutlet over rice), ten-don (tempura over rice), una-don (grilled eel over rice), and more. It is convenient and delicious!

Mochi (rice cakes)

Mochi is made by pounding steamed rice and forming it into different shapes. There are various ways to enjoy mochi: small pieces of mochi served with grated white daikon radish and soy sauce (karamimochi); mochi topped with sugar-mixed soybean powder (kinakomochi); mochi covered with red bean paste, and more.

Kiritanpo

A specialty of Akita Prefecture, kiritanpo is mashed, cooked rice shaped around a stick and grilled. Kiritanpo is typically enjoyed as a hot pot dish or with other simmered dishes, but can also be grilled with a miso sauce. The practice of eating grilled mashed rice on a wooden piece exists all over Japan, but the tradition of eating it in a hot pot is considered to have originated in northern Akita Prefecture.

Take a Guess Answer: The number of rice grains depends on the rice variety, but it adds up to approximately 3,250.