TRG Info and Advice

Japanese sake (rice wine)

The History of Japanese Sake

The origin of Japanese sake can be traced back to the Age of the Gods, where references to it are found in the 3rd Century Chinese book, Records of Wei: An Account of the Wa. Sake making, with rice as the main ingredient, started when wet rice cultivation was introduced to and took root in Japan (between the Periods of Jomon and Yayoi), and sake brewing spread from Kyushu and the Kinki Region (in the west and central part of Japan) to the rest of the country. At that time, sake was processed with the most primitive method, “kuchi-kami” (literally: mouth-chew), where cooked rice was chewed and converted to sugar with the help of enzymes present in saliva, and natural yeast helped with fermentation. In Japanese, the act of brewing sake is called “kamosu”, which reputedly originates from the word “kamu” (to chew). Only female miko, who serve gods in shrines, were qualified to do kuchi-kami, so sake might have been originally brewed by women. In the Nara Period (700’s), a brewing department called “Sake no Tsukasa” was established. They facilitated a sake-brewing system for the government, and sake-brewing technology began to develop.

At the beginning of the Heian Period (from late 8th Century to the early 9th Century), some records indicate that sake was brewed with almost the same methods as today. It was not available to everyone, however, and was consumed mostly by the nobility. Sake was, also, brewed for special occasions on celebrative days such as agricultural rituals and harvest festivals, and consumed after being dedicated to the gods. In the middle of the Muromachi Period (early 15th Century), sake was brewed in temples and promoted as “soubou-shu” (sake made in temples). As time passed, and urbanization and commercial activities advanced, sake became more widely distributed as a product with the same economic value as rice. Temples and shrines started to brew more sake, breweries prospered and Kyoto became the center for sake brewing. People started to drink sake on a daily basis, not only on special occasions. The sake brewed at temples and shrines had to be of good quality, because it was for honoring gods. That led sake brewing technology to develop to a greater extent and its characteristic technology was almost complete by the end of the 16th Century.

In the early Edo Period (early 17th Century), sake was brewed at five different times throughout the year, but by the middle of the Edo Period, people discovered that winter’s low temperatures produced the best sake. From then on, sake was brewed in mass during this optimal season and then stored. This resulted in the emersion of a group of master sake brewers (touji), whose purpose was to brew sake only in winter. At the same time, innovative methods were developing, like those to improve heat pasteurization at low temperatures to keep sake longer, and allegation “hashira shochu“ (meaning: pillar shochu, the addition of alcohol) to control fragrance and lower the risk of acidification. Shops which both brewed and sold sake appeared, making it accessible to the common people. A record tells that there were about 27,000 sake breweries around Japan at the end of the 17th Century, and sake brewing was considered a major industry. During the Meiji Period (1868-1912), people started to realize that scientific knowledge is essential to brewing good sake, and by the Showa Period, all types of equipment and measures were available. Nowadays, technology has developed to an even greater extent and better equipment is available, but there are still complex brewing methods, which machines can never master. The techniques and knowledge fostered by the touji sake brewers, therefore, are still required.

After hitting a peak of 1,766,000kl in 1973, the consumption of Japanese sake began to decrease. In 2011, sake consumption was down to 603,000kl, a drop of 65.9%. The number of sake breweries, also, was 4,021 nationwide in 1955, but declined to 1,684 in 2012, a 40% decline from the peak. However, the consumption of premium sake brewed in comparatively small amounts, is increasing little by little. Since Japanese cuisine has been attracting more and more people in recent years, the export of Japanese sake, mainly premium sake, is rising! Its export volume doubled from 8,270kl in 2003 to 16,202kl in 2013, and its export value tripled from 39 billion yen in 2003 to 105 billion yen in 2013.

What is sake?

Sake is an alcoholic beverage produced from rice and water since ancient times, which can be also used as a seasoning agent. Sake is also called seishu. It contains an average of 15% alcohol.

Sake made from rice is not just an alcoholic drink for Japanese people. It is deeply rooted in agricultural rituals of rice cultivation and was developed as an offering for dedicating to gods. Rice is a Japanese staple, and in other words, a source of life for Japanese people.

When people pray for the rich cultivation of rice, they dedicate sake (omiki) and mochi rice cakes made from glutinous rice, and when conducting rituals at the time of harvest, they offer the just-harvested rice. Sake is considered the most important offering dedicated to gods and is essential in festivals. Rituals are followed by a banquet called “naorai”. People take the offerings of rice and sake down from the alter, and eat and drink them in front of the gods. By consuming the food and drink in which divine power dwells, they believe they can take in the energy of the gods.

Sake is brewed by unique methods, and categorized as alcohol like wine and beer. Just like grapes are divided into ones for brewing wine and ones for eating, there is a special type of rice called “shuzo kouteki mai” that is suitable for sake making.

Good sake is said to have a similar taste to good quality wine when consumed cold. Sake is, therefore, sometimes entered in wine tasting exhibitions and awarded prizes. There is mass-produced sake that is sold nationwide, but there are, also, local sake breweries all over Japan. These regional factories have various, unique brewing methods, and produce different tastes peculiar to the area, dependent upon the quality of rice and water. This kind of sake is called “jizake” (regional or local sake) and it is estimated that there are about 5,000 different brands.

Rice, the main ingredient of sake, does not contain sugar, so koji mould is added to convert the protein in rice to sugar, and the enzyme in koji mould helps with the glycation of rice. Yeast is, then, added and the mixture is allowed to ferment slowly. Since glycation and fermentation take place at the same time in the same container, this process is called multi-parallel fermentation. This process is unique to sake, and is a complex method that requires extreme skill.

Sake is a rare alcoholic drink which tastes good either cold or warm, and you may enjoy it at a wide range of temperatures, from 5℃ to 55℃, unlike beer and wine. In Japan, a country steeped in rich nature, a lavish, sake-and-nature-appreciation culture has been nurtured. In spring, people enjoy sake at cherry blossom viewing parties. In summer, on the last day of June, people drink “Nagoshi no sake” to purify themselves from the accumulated foulness of the six months since New Year’s, and to get through the hot summer. In autumn, people enjoy sake while viewing the beautiful autumn moon, and in winter, while viewing the falling snow.

How to Brew Sake

1.Rice polishing and steaming: polished and rinsed brown rice is steamed. The cooked rice is used to make koji mold, and to prepare shubo, or moto (fermentation starter), and moromi (rice mash).

2.Make koji by adding koji mold to steamed rice. Koji helps convert the proteins in rice to sugar when added to shubo and moromi.

3.Shubo is a mixture of steamed rice, water, koji mold and yeast, in which yeast is mass-cultured to promote the fermentation of moromi.

4.From this point, sandan jikomi, a process unique to Japanese sake brewing (with its 3-stage fermentation process) takes place. Moromi is prepared in three stages, and yeast culture is promoted while preventing contamination.

5.Koji mold, steamed rice and water are added to shubo, and moromi is prepared. This moromi will be unrefined sake.

6.Moromi is pressed after more than 20 days of fermentation, and divided into sake and sake lees. Just pressed sake is filtered, heated (hiire) and bottled. After 60 days of preparation, the sake is ready.

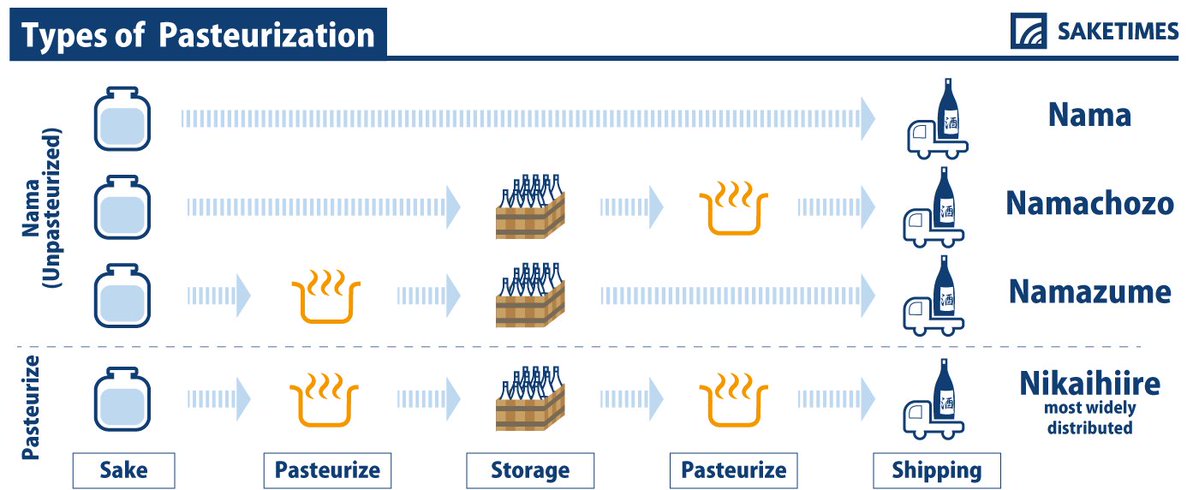

Pressed sake is pasteurized at around 65℃ and the enzyme effect is stopped. Heated sake is generally stored over summer and shipped starting at the beginning of autumn. Stored sake contains about 20% alcohol, but before shipping, water is added and the alcohol level is lowered to around 15%. Sake is heated again before bottling, so it is normally heated twice.

Types of Sake

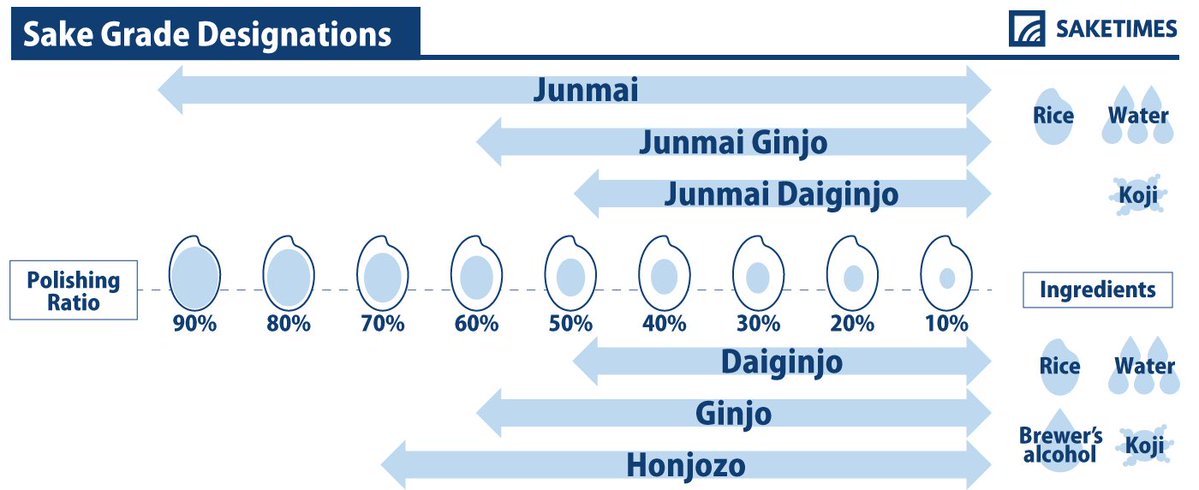

Ginjoshu

Ginjo-shu is sake brewed slowly at low temperatures of 5-10℃,with rice polished to less than 60% of its original size, rice koji mold and water; or rice, rice koji mold, water and distilled alcohol. The distilled alcohol works to control the taste of the sake, and releases the ginjo fragrance agents like apple, melon and banana, which tend to stick to undissolved yeast and rice. Ginjo-shu features a fruity, glamorous fragrance and sophisticated flavor. It is best served cold (5-10℃) or at room temperature.

Daiginjoshu

Daiginjo-shu is produced from rice polished to less than 50% of its original size, rice koji mould and distilled alcohol. It has a distinctively refined aroma and flavor, and the color is especially good.

Junmaishu (pure sake)

Junmai-shu is pure sake produced only from rice, rice koji mould and water without sub-ingredients such as distilled alcohol, sugar, acidic agents, and others. Most of junmai-shu is rich in rice flavor and somewhat heavy. Tasty at a variety of temperatures: cold, room temperature, or warm (5℃-25℃).

Junmai Ginjoshu

Junmai Ginjo-shu is pure sake produced from white rice polished to less than 40% of its original size and rice koji mold.

Junmai Daiginjoshu

Junmai Daiginjo-shu is pure sake made from white rice polished to less than 50% of its original size and rice koji mold.

Honjozoshu

Hon Jozo-shu is made from rice, rice koji mold and a small amount of distilled alcohol. With the addition of distilled alcohol, the tartness becomes softer and the overall taste is drier and crispier. The flavor of rice becomes well-balanced, too. Tasty at a variety of temperatures: cold, room temperature or warm (5℃-18℃ or 24℃-40℃).

Futsu (jozo) shu (regular sake)

Futsu (jozo) shu is sake pressed after adding distilled alcohol (slightly more than Honjozo-shu). Some Futsu (jozo) shu is made with sugar and acidic agents. It tastes subtly sweet and has a light flavor. Best served warmer than room temperature (10℃-23℃, 35℃-50℃).

Tokubetsu (Special) Junmai-shu

This is sake made from white rice polished to less than 60%. Other ingredients or special methods vary and are unique to each sake brewery.

Tokubetsu (Special) Honjozo

This sake is made from white rice polished to less than 60%, rice koji mould, brewing alcohol and water. It is made using special methods.

Namazake

Namazake is unpasteurized sake, which is not heated after pressing. When stored in a refrigerator, you may enjoy its just-pressed, fresh flavor for a long time.

Nama chozo-shu

Nama chozo-shu is sake placed in storage without heating and is pasteurized only once, just before bottling and shipping.

Hiyaoroshi (Namazume-shu)

Hiyaoroshi or namazume-shu is pasteurized only once before being stored in sake tanks, aged over summer, bottled and shipped.

Genshu

Gen-shu is sake to which water is not added after storing, and has a rich flavor. It contains about 20% alcohol and features a powerful taste.

Kijoshu

In general, sake is made from rice and water in the ratio of 100:130, but kijoshu is made from rice, water and sake in the ratio 100:70:30, so it is sake prepared with sake. It features a rich taste of balanced, mellow sweetness, and tartness. When stored, the color gradually changes to amber.

Nigori-zake

Nigori-zake is white, cloudy sake with moromi mash filtered through cloth with a coarse texture. Nigori-zake, which is not heated or pasteurized at the time of shipping is also called kassei-shu. With enzymes and active yeast, you may enjoy a bubbly mouthfeel.

Ori-zake

Ori-zake is similar to nigori-zake, but the brewing method is a little bit different. There is sediment of a mixture of koji mould and yeast left in the bottom of sake tanks, even if moromi mash is filtered through tightly woven cloth. Ori-zake is white, cloudy sake with sediment.

Kounoudo-shu (High-concentration sake)

Kounoudo-shu is sake which contains a high volume of alcohol, between 24% to 36%.

Choki Chozoshu (Koshu) [sake stored over a long term]

Wine aged over 100 years or whiskey aged over a long term has a mellow, rich taste. Sake usually matures in a year, but ginjo-shu tastes mellower when aged for a long term. Koshu aged for 2, 3 or 5 years are available. Tasty at a variety of temperatures: cold, room temperature and hot.

Ki-ippon

Ki-ippon is pure sake made in a single brewing factory.

Kimotozukuri

At old breweries with a long history, lactic acid bacteria resides in sake making factories over a long time, so it naturally mixes with shubo (yeast starter) and promotes sake-making by producing lactic acid. Sake made by using natural lactic acid bacteria is called kimotozukuri.

Yamahai jikomi

In the traditional sake making method, “kimoto zukuri,” it is a laborious process to grind down rock-hard rice koji mould after it has been cultured. This process is called “yama oroshi.” Grinding down a mountain of rice koji mold using a large wooden paddle-like tool is extremely difficult. In the Meiji Era, however, the government established The National Research Institute of Brewing, and various studies were conducted. At the end of the Meiji Era, the Institute announced that, with or without yama oroshi the content of sake does not differ very much. Thus, the difficult task of beating sake rice was determined unnecessary. The sake-making method without yama oroshi is called “yama-hai zukuri”, because yamaoroshi was discontinued (in Japanese: hai-shi).

Taruzake

Taruzake is sake stored in a keg, which imparts a woody flavor. The keg is usually made of cedar, and Yoshino cedar is considered the best. Taruzake has some varieties: one is hon-nidaru, which is wrapped with colorful matting, and another is a wood-grained cask without straw matting.