TRG Info and Advice

Wagashi: Traditional Japanese Confectionery that Delights the Senses

Have you ever heard of or eaten wagashi? Wagashi are traditional Japanese-style snacks, including sweets made with sugar, syrup, and “an” (sweet red bean paste), as well as, snacks flavored with salt and soy sauce, such as senbei and arare (rice crackers), and dango (dumplings).

Jo-namagashi: The Essence of Wagashi

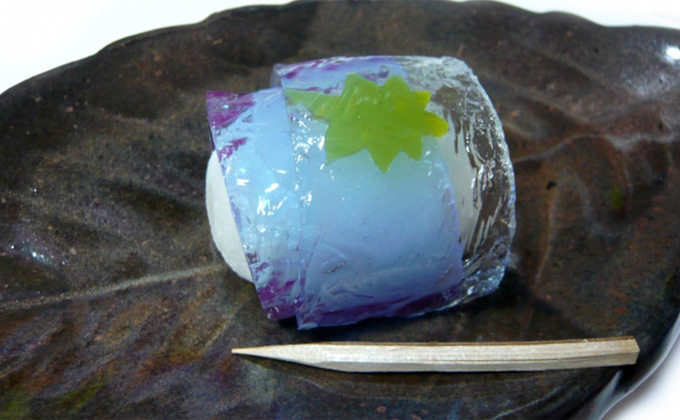

If you visit a conventional wagashi shop, you will encounter a colorful array of sweets displayed in the showcase. These pleasantly colored, dainty pieces of confectionery are called jo-namagashi (literally: superior, fresh sweets), which are mainly served at tea ceremonies, paired with the slightly astringent flavor of matcha (thick green tea). Carefully crafted with various colors and shapes, jo-namagashi captures the changes in seasons.

Each season has sweets which are made only in that season. Some sweets are deeply associated with annual events, while others are uniquely developed in accordance with local, everyday life.

How to enjoy wagashi

Jo-namagashi are meant to engage all five senses, so a lot of thought is given to their designs and names. In addition, each sweet skillfully makes an allusion to classical literature, history, cultural climate and/or seasonal changes.

・Taste: enjoy the deliciousness

・Smell: sense the aromas of the ingredients

・Touch: feel the texture, mouthfeel and the sensation of cutting the sweet with a kuromoji (black willow) pick.

・Sight: appreciate the appearance

・Hearing: hear the name [of the wagashi], consider its background and meaning

The History of Wagashi

It is only recently that wagashi, the collective name for Japanese-style confections, became common (post WWII). Until then, snacks used to be simply called “kashi.” The colorful sweets in a plethora of shapes that can be seen today appeared in the Edo Period (1603-1867).

In ancient times, kashi used to denote fruits and nuts, and was also read kudamono (fruits), not kashi. Even today, “mizugashi” (literally: water snack) means fruits, and this helps to prove the origin of the word. In a book compiled in the 9th century to record items given to the Imperial Court from all over Japan, lists of the names of fruits and nuts, such as bayberries, chestnuts, tachibana citrus, akebia fruits, Japanese pears, and hazel nuts, among others, can be found.

After rice production expanded, mochi (rice cakes) and dango (dumplings) came into existence. Made by hand from rice, millet, and other grains, these are the prototypes of present-day wagashi. A book from the 8th century lists names of snacks, including Mamemochii (soy bean mochi), Azukimochii (red bean mochi), and irimame (roasted beans).

In the 7th century, karakudamono (Tang Dynasty’s sweets) were brought from China. Karakudamono are sweets made by kneading rice powder and flour, shaping the dough into various shapes and then deep-frying it. During the Edo period, these sweets disappeared from daily life, but they are still dedicated to gods as offerings at shrines such as Shimogamo Shrine in Kyoto and Kasuga Shrine in Nara.

During medieval times (the Kamakura Period and Muromachi Period), Chinese snacks called Diang Xin were brought to Japan and are considered the origins of manju (steamed buns with sweet fillings) and yokan (thick red bean jelly). At that time, many Buddhist schools were established, and monks who studied in China brought back culture and dietary habit as well as doctrines. Among them, Zen monks introduced the tea (matcha) drinking habit and Diang Xin (snacks eaten between breakfast and dinner).

Later, in the Sengoku Period (1491-1573), cultural exchanges with the Portuguese and Spanish merchants and missionaries began. These exchanges introduced treats such as kasutera (castella: sponge cake) and konpeito (confeito: candy). As a result, larger amounts of sugar and eggs became more familiar ingredients in snacks.

Wagashi, influenced by the Chinese and Europeans, was transformed from simple, rustic snacks into sophisticated jo-namagashi in Kyoto, which was home of the Emperor and the center of economics, religion and tea ceremony traditions. The sweets, brought to perfection, spread nationwide to castle towns via the city of Edo where the shogun lived. People-driven culture was nurtured during the Bunka and Bunsei eras (1804-1830) of the Edo Period, when many tea ceremony aficionados appeared among common people, and that further accelerated the development of wagashi.

Wagashi Ingredients

Most wagashi ingredients are plant-based, which is one of the main features of wagashi. Only a few kinds of wagashi are made using animal-origin ingredients, such as eggs for dorayaki (two round, small pancakes with red bean paste fillings).

・Rice: non-glutinous rice / glutinous rice

Rice is processed into a wide variety of powders, then prepared in different ways in order to give the desired texture to the sweets/snacks.

・Wheat: flour

・Beans: red beans (azuki), white beans, pea beans, green beans, green peas, green soybeans (zunda)

The color of red beans was once believed to ward off evil and sickness.

Red beans are boiled with sugar, then mixed well to make a paste. An is used as both a filling and a coating.

Red bean pastes come in a variety of styles, including coarse tsubu-an with the beans still partially intact, and mashed fine koshi-an with its smooth texture. Red bean paste might be an acquired taste, but wagashi is not complete without it!

・Sugar: white sugar, brown sugar, wasanbonto, etc.

Made from the Chikuto variety of sugarcane, wasanbonto sugar features fine crystals and a melt-in-your-mouth texture.

It was not until the later stages of the Edo Period when sugar production came into full swing. Until then, food was sweetened with honey, syrup, and “amazurasen,” which was made by straining Japanese ivy sap and boiling it down.

・Agar: Made from seaweed, it coagulates after being dissolved in boiling water.

・Kuzu (kudzu): Protein taken from kudzu roots

・Yam: Grated when used

Snacks and Annual Events

Around the world, sweets are an important aspect of seasonal events: Christmas cakes in Japan and Europe, mooncakes in China, gulab jamun in India and other countries, kulich in Russia and other countries, qatayef in the Middle East and hamantash in Israel, just to name a few.

In Japan, too, sweets play an essential role in seasonal and traditional events, representing prayers for health, bountiful harvests and prosperity, as well as providing a sense of the season.

Shogatsu: Hanabiramochi (flower petal rice cake)

On a round, flattened piece of mochi, with a diameter of about 15cm, a small hishi mochi (Trapa japonica cake) colored with the bitter juice of red beans, rich white miso paste, and a soft-boiled burdock root stick are placed in order. The rice cake is then folded before being consumed. It is believed that this sweet originated from a court ritual to wish for longevity by eating something hard.

Hinamatsuri (Doll Festival): Kusamochi (green mochi), Hishimochi (diamond-shaped mochi), Hina-arare, Hikichigiri

Kusamochi was originally made from Jersey cudweed, but is now made mainly from Japanese mugwort. Kusamochi was once thought to drive out evil spirits and protect against illness. No-one knows when, but at some point, Kusamochi became a diamond shape, and was piled with a white mochi layer.

Hikichigiri is a round mochi cake with a dollop of red bean paste on the dented top, which is mainly consumed in Kyoto. The tip seems as if it was torn off and looks like a handle.

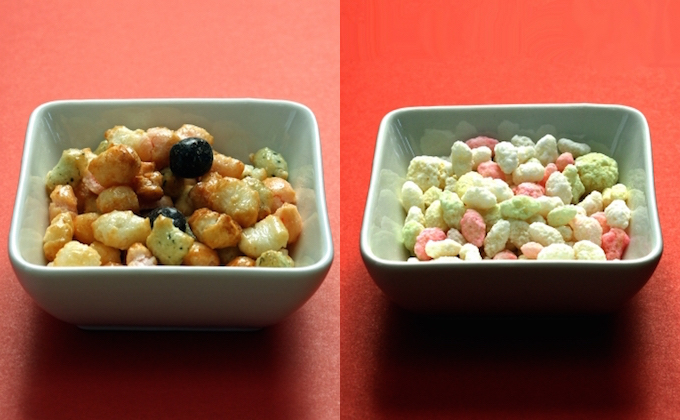

The name hina-arare evokes different images depending on whether you are in Kanto or Kansai. In the Kanto region, hina-arare are puffed, non-glutinous rice snacks, which are colored and sweetened with sugar. In the Kansai area, however, arare are small balls, about one centimeter in diameter, made from glutinous rice. They come in several flavors, including soy sauce, salt, chocolate and others.

Tango no Sekku (Boys’ Festival): Kashiwamochi, Chimaki

Oak leaves do not fall until new leaves sprout, so they are considered an auspicious item that brings family prosperity.

The habit of eating Chimaki (made by wrapping pounded, steamed rice powder, or kudzu powder in five long, striped bamboo leaves and then steaming them), supposedly originated from an incident in ancient China. A famous poet Qu Yuan had served the King in the 4th century BC, but was banished during a conspiracy. In despair, Qu Yuan threw himself into a deep river pool. After that, on the anniversary of his death, people would throw in a rice-stuffed piece of bamboo. One day, the ghost of Qu Yuan appeared in front of the people and asked them to wrap the bamboo rice with a chinaberry leaf instead, and bind it with threads of five colors, because a dragon was eating their offerings but it hated chinaberry leaves. So, people prepared offerings as they had been told and this is said to be the origin of chimaki.

Ohigan (Higan): Botamochi, Ohagi

Balls of steamed and lightly pounded rice are coated with red bean paste. Those made in spring are called “botamochi,” after the seasonal flower botan (peonies), and those made in autumn are called “ohagi,” after hagi (Japanese clover). Those in summer and in winter are called “yofune” (night ship) and “kitamado” (north window) respectively. Why botamochi/ohagi are associated with Higan is not clear, but they are said to have originally been offered to gods in hopes of a bountiful harvest in spring and with thanks for a bumper crop in fall.

Kajo no Hi: Manju, Yokan

The origins of Kajo no Hi (day of auspiciousness) are obscure, but this custom turned into one of the most important Tokugawa Shogunate’s events in the Edo Period, and was gorgeously celebrated. Thousands of rice cakes and red bean jellies (yokan) were displayed in the great hall of Edo Castle and given by the Shogun to daimyo (feudal lords) and hatamoto (direct feudatories of the Shogun). This custom almost disappeared after the Meiji Period, but today, the Japan Wagashi (Japanese Sweets) Association has designated the day as “Wagashi Day.”

Nagoshi no Harae: Minazuki

This is a triangular Uiro cake with sweet red beans scattered on top. The red color of the beans is considered to drive out evil. One theory claims that the triangular shape imitates the wand with two paper streamers used at rituals in shrines, while another claims that the cake is triangular in honor of the event when ice is delivered from the ice house to the Imperial Court or the Shogunate.

Moon viewing: Dango (dumplings)

Round-shaped dumplings are offered to the moon in the Kanto region, while taro-shaped dumplings, half-wrapped with an, are offered in Kyoto and Osaka. Taro-shaped dumplings are derived from the taro harvest season at this time of the year.

Shichi-Go-San: Chitose-ame (a thousand years candy)

Chitose-ame is a long, narrow stick of candy colored in red and white, packaged in a bag with auspicious illustrations such as a turtle and a crane, plus pine trees, bamboo, and plum flowers. As the name suggests, the candy is prepared in hopes of well-being and longevity. It is presented to seven, five, and three-year-old children who are being recognized for their age-appropriate cultural milestones.

Wagashi Parade

There are several ways to categorise wagashi. One way is to divide them into three groups: namagashi (fresh wagashi), han-namagashi (half-fresh wagashi), and higashi (dry wagashi), based on the water content.

Namagashi contains over 30% water, han-namagashi: 10-30%, and less than 10% for higashi.

◼︎ Namagashi

Ohagi

Steamed rice is pounded and coated with an, kinako (soybean powder), and sesame, among others.

Sakuramochi

Sakuramochi is mochi cake (usually dyed light pink) wrapped with a salted cherry leaf. In the Kanto region, it is prepared by mixing and kneading flour, sugar and shiratamako (made by grounding glutinous rice while adding water, and drying the sediment), baking the flattened dough on an iron plate, and then wrapping or coating an with it (right). In Kansai, steamed domyojiko (coarsely-ground powder of steamed and dried glutinous rice) are formed in the shape of rice-straw sacks with a red bean paste filling, and then wrapped with a cherry leaf (left).

Suama

Joshinko (fine-textured, non-glutinous rice powder) is kneaded, separated into pieces and steamed, sugar is then added, little by little, while pounding the mochi.

Yubeshi

A mixture of yuzu citrus peel, glutinous rice powder, non-glutinous rice powder and sugar is steamed, wrapped in a bamboo skin, and formed into a stick shape. Yuzu-flavoured mochi cakes, or yokan, are also called yubeshi.

Dango (dumplings)

Steamed balls of glutinous or non-glutinous rice. In many cases, balls are on bamboo skewers. They are coated with an, kinako or grilled and glazed with soy sauce.

Dorayaki

A batter of flour, eggs, sugar and water is baked in a round shape on an iron pan, like a miniature pancake. An (red bean paste) is then placed between the two pieces of the pancake. This is Doraemon’s favorite snack.

Taiyaki

Flour batter is poured onto the sea bream-shaped pan, topped with an, and grilled. The fillings are widely varied from an, to custard and chocolate. The members of Aerosmith are huge fans of taiyaki, by the way.

Castella (kasutera)

The recipe is said to have been brought from Portugal in the late 16th century. A mixture of sugar, flour, honey, syrup, milk and other ingredients is poured into a mold, and baked in an oven. Kasutera originated from Europe, but as time passed, it was transformed to become a unique Japanese sweet, and it is now categorized as wagashi.

Yokan

Yokan is made by dissolving kanten in boiling water, adding sugar and an to it and boiling down the mixture. The thickened mixture is poured into a mold and coagulated (neri-yokan). The one with a finer texture made with more water added is called mizu-yokan (literally: water yokan), and the one made by kneading and steaming the mixture of azuki powder, flour and sugar is called mushi-yokan (literally: steamed yokan).

Kuzukiri

Kudzu powder is boiled until translucent. Coagulated kudzu is then cut into thin strips and chilled. It is served with brown sugar syrup.

Mitsumame/Anmitsu

Diced agar, sweet apricots and red peas are dressed with honey or brown sugar syrup. If mitsumame is topped with an, it is called anmitsu. There are various kinds of mitsumame: fruit mitsumame topped with fruit, cream mitsumame topped with ice cream, shiratama mitsumame topped with shiratama dumplings, and more.

Nerikiri

Also called jo-namagashi, nerikiri is a representative of wagashi. An is kneaded well with sugar, then glutinous rice and gyuhi are added as thickener. Kneaded an is then beautifully shaped by pushing it into a mold or sculpturing. Rich in colour, nerikiri express the four seasons, and are often served at tea ceremonies or celebratory occasions such as weddings.

An Doughnut

A kind of Japanese-style doughnut, made from a batter of flour, water, sugar, butter, eggs and other ingredients, is shaped and then filled with a red bean paste, and deep-fried.

Kuzumochi

Kudzu powder is heated and kneaded with water and sugar. In Tokyo and its surrounding areas, kuzumochi is made by fermenting flour with lactic acid, washing the flour to remove the tartness and fermenting odor, adding hot water, and then steaming. This is the only wagashi which is a fermented food. Both kinds of kuzumochi are served with brown sugar and kinako.

◼︎ Han-namagashi

Monaka

Flattened, kneaded glutinous rice is baked using molds, then an is placed between the two. Legend has it that white, round mochi served at the time of the harvest moon viewing in the imperial court looked like the moon reflected on a pond, and the wagashi was named as “monaka no tsuki” (moon in the middle) in honour of a poem written about the moon in mid-autumn. Monaka with ice cream and an is also popular.

Gyuhi

Pure white and soft, gyuhi is a mochi-like sweet made by kneading shiratamako, sugar, and syrup. It is sometimes used to wrap an or yokan.

Amanatto

Red beans and other beans are boiled down after being soaked in sugar syrup, and coated with white sugar. There are amanatto made from chestnuts and sweet potatoes, too.

◼︎ Higashi

Rakugan

Grain powder made from glutinous/non-glutinous rice or others is mixed with sugar and a little amount of water and syrup, and the mixture is kneaded well. The kneaded mixture is placed in wooden molds and shaped, heated, and dried. A sophisticated wagashi, rakugan can deliver the subtle flavors of the ingredients.

Okoshi

The Okoshi mixture is made from glutinous rice, non-glutinous rice, millet and other ingredients (steamed, dried and roasted), mixed with beans and sesame. The mixture is covered with boiled-down syrup, rolled out and cut into small blocks.

Konpeito

A sugar candy with characteristic tiny bulges, konpeito is the same sweet made in Portugal today named confeito (candy). It is made by coating cores (which used to be poppy seeds and are currently caster sugar) repeatedly with sugar syrup in a rotating, tilted tub. This process takes two weeks to complete.

Karinto

A mixture of flour, sugar and water is deep-fried and coated with brown sugar syrup or white sugar.

Arare/Okaki (rice crackers)

Baked or deep-fried snacks made mainly from glutinous rice. It was already being made by cracking kagamimochi in the Heian Period (794-1185).

Succumb to the sweet allure of wagashi from all over Japan, at the National Confectionery Exposition: Kashihaku.

If you have a sweet tooth and are a big fan of wagashi, why not visit the National Confectionery Exposition?

Held once every four years in a different city each time, the Exposition is the largest fair of its kind in Japan with over a hundred years of history. At this event, confectioners gather from all parts of Japan, and skillfully made sweets are displayed and sold, while elaborate sugar crafts are exhibited.

The last one, the 27th Expo held in Mie Prefecture, showcased 1,800 different wagashi items of over 530 confectioners from Hokkaido to Okinawa.

The best items are presented with awards such as the Honorary Presidential Award by an imperial family member, and the Prime Minister Award. These prizes are considered a great honor among confectioners.