TRG Info and Advice

Annual Events and Folklore Customs in Japan Part 1

Since ancient times, the Japanese have cherished seasonal events and festivals. The New Year is celebrated with zouni (soup with rice cake) and osechi (special New Year’s dishes), decorations of kagamimochi (piles of big, round rice cakes) and shimenawa (elaborate entrance ropes), and the first visit of the new year to a shrine to pray for health and good luck. At the hina doll festival in March, hina dolls are displayed to wish for girls’ well-being and happiness, and when cherry blossoms come into bloom in mid-spring, many merrymakers have cherry-blossom-viewing picnics. At the star festival in summer (tanabata), people write wishes on a piece of paper (tanzaku) and hang them on cut branches of bamboo. In autumn, we appreciate the splendor of the harvest moon in the very clear sky; and on the winter solstice, we eat pumpkins (acorn squash). These annual, customary events and practices persist across Japan even today.

Japanese people’s lives used to be centered on farming, and so, agricultural rites marking the seasons were brought about to pray for bumper crops and to show appreciation for the harvest. Some events are an integration of Chinese customs and Japanese ones. These events take place in seasonal cycles, driving away evil spirits and offering prayers for well-being and fertility. Many of the traditional events seen today were originally carried out in the imperial household, later being passed on to samurai households, and eventually taking root in common people’s lives.

As lifestyles change with the times, so, too, have these agriculturally-based events transformed or disappeared, and in many cases, especially in urban areas, their original purpose has been diminished or forgotten. Annual events, however, are still a part of most Japanese people’s lives, with or without awareness, as they appear in the form of traditional dishes. In addition, foreign holidays such as St. Valentine’s Day, Mother’s Day, Halloween and Christmas have been adopted into Japanese life, especially by younger generations, although they have little religious significance or connection to the original purpose.

Annual events, which bring color, will accent your life in Japan, and the more you know about them, the more you will enjoy them. Events and festivals differ from place to place, and there are many events unique to each area. Why not visit many places and experience them for yourself?

Annual Events and Folklore Customs (January—June)

January

1st of January: Oshogatsu

At the beginning of the New Year, families gather, give thanks for the previous year’s harvest and pray for next year’s bountiful crop. Pine decorations serve as guides for Toshigami (deities of the year) so the god can visit the house without getting lost, and the shimekazari divides the sacred space, where the Toshigami are enshrined, from the secular areas. Deities are drawn to the two big, round Kagami-mochi (rice cakes). People take a sip of otoso, which drives away evil spirits and brings health, and eat the zouni soup with a rice cake. The rice cakes in the zouni soup are taken from those offered to Toshigami, so that the power and energy of Toshigami can be shared.

7th of January: Jinjitsu (Day of Humans)

In ancient China, there used to be a custom for divining the future by assigning animals to the first six days of the New Year, and the seventh day was set aside for human beings. It was later celebrated as Jinjitsu, one of the five seasonal observances. As is the custom (adopted from China), people traditionally eat a soup prepared with seven kinds of ingredients on this day, to wish for good health. This Chinese tradition is intertwined with an ancient Japanese custom of picking up and eating young grass to get its strong energy, and the January 15th imperial court’s custom of eating rice porridge prepared from seven different grains. Eventually, these customs combined into the practice of eating rice porridge made using seven kinds of young grass (nanakusa gayu). The grasses are water dropwort, shepherd’s purse, jersey cudweed, chickweed, henbit, turnip greens, and daikon radish greens. Eating nanakusagayu is believed to bring protection from illness and bad fortune.

11th of January: Kagamibiraki (breaking kagamimochi)

Kagamimochi offered to deities are taken down and consumed. The date on which to break the kagamimochi differs from place to place, but it is commonly the 11th of January. You cannot use a knife to cut the kagamimochi where deities are drawn, so a mallet is used instead. Broken pieces of mochi are put into zenzai (sweet red bean soup), or used in other dishes.

15th of January: Koshogatsu (Little New Year)

According to the old calendar, on the 15th of January will be the first full moon of the year, so it is customary to eat rice porridge made with sweet red beans. In the past women could finally take a break around this time, after working so hard cleaning and preparing food for the New Year holiday, and this is why Koshogatsu is also known as Onna Shogatsu (the women’s New Year). On this day, a bonfire is made using the New Year’s decorations, the previous year’s amulets, and so on, to mark the departure of Toshigami. It is believed that if you eat mochi baked on the fire and touch the smoke, you can spend the year in good shape. There are many other widely held beliefs, too. For example, if you burn the year’s first piece of calligraphy, your handwriting will be refined. This bonfire was originally called “Sangiccho (three ball canes),” because a set of three canes used in court nobles’ ball game were burnt. Since then, it has changed into Sagicho, but in some areas, Sagicho is called something different, such as Tondo and Dondo.

Coming-of-Age Ceremony

In Japan, children legally become adults at the age of twenty. The Coming-of-Age Ceremony, mostly hosted by local governments, is held to mark the passage, and to celebrate the transition from child to adult. The 15th of January became a national holiday named the Coming-of-Age Day, and today, it is observed on the second Monday of January. On that day, you can see many young men and women clad in gorgeous furisode (long sleeved) kimonos, hakamas, or brand-new suits.

February

3rd of February: Setsubun

In the past, all of the days before the day when the seasons change (Risshun, Rikka, Risshu and Ritto) were called Setsubun. On the old calendar, Risshun was considered special because it marks the beginning of a new seasonal cycle, and so, the setsubun in Spring gradually became the most important one. On that day, we throw beans to drive away evil, represented by demons (oni), and wish for good health by eating the number of beans corresponding to your age. It is believed that you can shield yourself from evil spirits if you display the head of a sardine skewed with the tip of a holly branch at the entrance. Eating a thick sushi roll on Setsubun is relatively a new custom, which has become more common in the last thirty years.

6th of February: Hatsu-Uma (The First Horse)

Animal signs were once used as an indication of specific days, and each day was allocated an animal sign. Hatsu-Uma, the First Horse, is celebrated on February 6th, at all Inari shrines around Japan. To commemorate the day of the enshrinement of Inari Okami (a god of abundant harvest) on Mt. Inari, people pay a visit to an Inari shrine. This time of year is considered the best time to start farming. In many places, on Hatsu-Uma, the god of rice paddies is welcomed down from the mountains and into the village, and people pray for a bumper harvest prior to planting.

March

3rd of March: Momo no Sekku or Joshi no Sekku (Peach Flower Festival)

Joshi means the first Day of Snake in March. There used to be a custom of purifying with water in ancient China. That was integrated with Japan’s ancient tradition of purification by the waterside, an event where paper figures were thrown into rivers to drive evil spirits away. The hina doll festival is considered to have originated from this habit of throwing hina dolls into rivers. Intertwined with playing with dolls, people later started displaying dolls to pray for girls’ healthy growth in the Edo Period, and in some places in Japan, the dolls are connected to marriage. The hina doll festival is celebrated with peach flower sake and yomogi mochi (mugwort rice cake), both of which are considered symbols of a strong life force.

Around the 20th of March: Higan

Higan is a period of seven days, with the vernal equinox as the fourth day. Ancient people believed that the Pure Land of Perfect Bliss was situated in the west, and that they can go closest to the Land on the vernal equinox day, when the sun sets due west. Consequently, a Buddhist event in honor of the deceased was established: people visit ancestors’ graves, clean their Buddhist altars at home, and make offerings of botamochi/ohagi (sticky rice balls with a sweet red bean filling). Even before the introduction of Buddhism, festivals were supposedly held to mark the beginning of farming around this time of year since ancient times.

Shanichi in Spring

Shanichi is the Dog Day closest to the vernal equinox. Sha indicates a shrine where tutelary deities are enshrined. People make visits to their tutelary shrines and pray for rich harvests. Shanichi was considered the day to welcome the deities of rice paddies and mountains, who govern agriculture, and was also considered the sign to start farming. There is another Shanichi in autumn, when people visit their tutelary shrine to give thanks for the harvest and to see off the gods of rice paddies and mountains. These customary events are no longer common.

From late March to May: Cherry Blossom Viewing

As many of you might be aware, many merrymakers throw parties under cherry trees, enjoying the beautiful pink sakura flowers, along with sake and food. Today, the word sakura mostly indicates the Someiyoshino variety, but sakura in olden times meant the mountain cherry flowers that bloom in the woods. Cherry flower viewing was originally the norm among court nobles. But, apart from that, farmers performed religious and agricultural rites, to welcome in the deities of rice paddies and to divine the year’s rice harvest, by throwing celebrations under cherry trees when flowers came into bloom. Cherry blossom viewing evolved into a pastime during medieval times, and became even more popular in the Edo Period.

April

Jusan Mairi

Boys and girls turning thirteen pay a visit to the Ākāśagarbha Bodhisattva, which is thought to have eternal wisdom, with the hope of receiving happiness and sagacity. It is custom not to look back after praying until you have passed through the torii or gate, or you might lose what you gained from the Bodhisattva. This Jusan Mairi event does not take place very often, but is more likely to be seen in the Kansai area.

8th of April: Hanamatsuri (Flower Festival)

The 8th of April on the old calendar is considered Buddha’s birthday, which is celebrated by setting up the florally decorated hanamido (flower hall), placing a statue of Buddha in the middle, and pouring amacha (sweet tea: Hydrangea macrophylla tea) over it. This event has a long track record as Buddhist. Among common folk, however, where there were customs of going to the mountains for cherry viewing and picnics, people would also arrange seasonal flowers at the entrance or tie them up with a bamboo stick to erect in the garden. This act was aimed at welcoming deities of rice paddies from the mountains prior to the start of farming. Also included were customs of commemorating one’s ancestors, and casting a spell to repel insects

May

Around the 2nd of May: Hachijuhachiya

The eighty-eighth day from Risshun (Beginning of Spring) is called Hachijuhachiya (the eighty-eighth night). This day is considered to be a good day for farming, such as sowing rice seeds or picking tea leaves. Tea leaf picking widely takes place around this time of year. It is said that you can spend the whole year in good shape if you drink the tea brewed from tea leaves picked on Hachijuhachiya day.

5th of May: Tango no Sekku (Festival for Boys / Children’s Day)

Tango no Sekku came from China, where rituals to drive away evil spirits were performed when illnesses and disasters started to prevail around the rainy season. In ancient China, an alcoholic beverage made with iris flowers was consumed, but in Japan, we take a bath with iris leaves and stems afloat in hot water. Chinese legend has it that carp swim up rapid streams and turn into dragons, and this is why carp streamers are raised high in the sky, to wish for social success. Families with boys also display samurai warrior dolls with armour, a helmet, and a sword, to pray for boys’ healthy growth. Tango no Sekku is celebrated with kashiwamochi (rice cakes with a red bean paste filling wrapped in oak leaves). Oak leaves do not fall until new leaves sprout, so they are considered an auspicious item that brings family prosperity. Another custom, that of eating chimaki (made by wrapping pounded, steamed rice powder, or arrowroot powder in five long, striped bamboo leaves and then steaming them), supposedly originates from an incident to commemorate Qu Yuan, an ancient Chinese poet. Today, Tango no Sekku is a designated national holiday called Children’s Day.

June

1st of June: Changing Clothes

The 1st of June marks the time to change uniforms, at schools or in offices, to the summer ones. Similarly, on the 1st of October, summer clothes are changed into winter clothes. In imperial households, according to the old calendar, clothes were changed on the first of April and October, following the Chinese custom of purifying through changing summer and winter clothes. Other personal articles such as fans were changed as well. In the Edo Period, there were four Changing Clothes days. As western clothes become the norm, clothes are, once again, changed only twice a year.

Around the 11th of June: Nyubai (Start of Rainy Season)

Around this time of year when the rainy season starts, ume plum trees bear a lot of fruit, and green ume plums begin to be sold at supermarkets. Preparing salty dried ume plums (umeboshi), umeshu (plum wine), and other plum-related things, is called “ume-shigoto” (ume plum work). Ripe, yellow plums are made into salty, dried umeboshi (pickled plums) and umezu (plum vinegar), and hard, green plums are made into umeshu, syrup, juice, and so on.

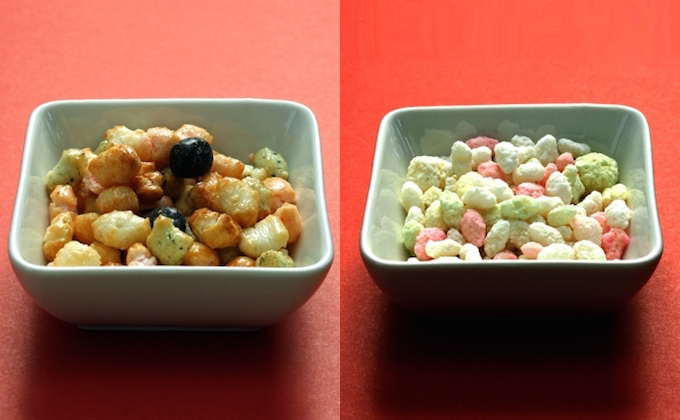

16th of June: Kajo no Hi (Wagashi Day)

The origins of Kajo no Hi (day of auspiciousness) are obscure, but there seems to have been a tradition of eating sweets and rice cakes after offering them to gods in order to ward off evil. This custom turned into one of Tokugawa Shogunate’s annual events in the Edo Period, which was gorgeously celebrated. Thousands of rice cakes and red bean jellies (yokan) were displayed in the great hall of Edo Castle and given by the Shogun to daimyo (feudal lords) and hatamoto (direct feudatories of Shogun). This custom of eating sweets also became common among regular people. Kasho no Hi almost disappeared after the Meiji Period, but today, the Japan Wagashi (Japanese Sweets) Association has designated the day as “Wagashi Day.”

30th of June: Nagoshi no Harae

The 30th of June, which is the halfway point of a year, is the day on which people try to wash their sins away, to get rid of any misfortune accumulated in the past six months, and to wish for well-being for the remainder of the year. White paper figures cut out in the shape of human beings are thrown into rivers. There is also a tradition of walking through Chinowa, a huge ring made of reeds, which is set up under torii gates or in front of the worship hall in shrines.

For Part 2 of this article, please click here.