TRG Info and Advice

The Power of a Name

Recently, my two oldest children banded together for a little early April Fool’s joke on me about Japan’s new era name, or gengo. “They announced it already, Mom! The new era will be called ‘Ua-kuchi-biru. It means ‘upper-lip.”

Now, at first I was flabbergasted! Why would Japan name an entire era Upper Lip? My overall impression of Japan is that it usually thinks things through thoroughly. But, then I remembered the English saying, “Keep a stiff upper-lip,” and gave the officials credit for both their international scope of knowledge, and for setting a stance of strong emotional restraint (very Japanese, btw, and totally opposite the US’s current emotional politics) for this new political period.

Those naughty children let me go on believing in their tomfoolery. I only found out I’d been duped when I tried to confirm my assumptions by asking a fellow hula dancer.

“What does the new era name “Upper Lip” mean?” I innocently inquired. She looked at me like I was nuts and said, “They haven’t announced the new name, yet, but it will most certainly not be Upper Lip.”

It was then and there that, for the sake of my pride and out of fear for my children’s bilingual prowess, I vowed to become a little more informed about Japan’s modern eras: names, dates and highlights.

The How and Why of Gengo

First, a quick note about gengo, and how and why they are chosen. Starting with the Meiji era, a “one-era, one-name” system was established and the number of years in each era directly coincides with the emperor’s reign. When an emperor dies or abdicates, a new name is chosen by a committee selected by the Prime Minister and that gengo is adopted at the time the successor ascends. This practice officially became a law in 1979 with the passage of the Era Name Law.

As for why an era needs a name, there are many theories. It is used on calendars, official records, and newspapers, so for some people it creates a daily reminder of the fact that Japan is a monarchy. Using the gengo to set a goal or theme for the nation as a whole is another way to unify Japan. According to Professor Kenneth Ruoff of Portland University, “It's a sort of a soft form of nationalism."

Meiji “Enlightened Rule” Era: 1868-1912

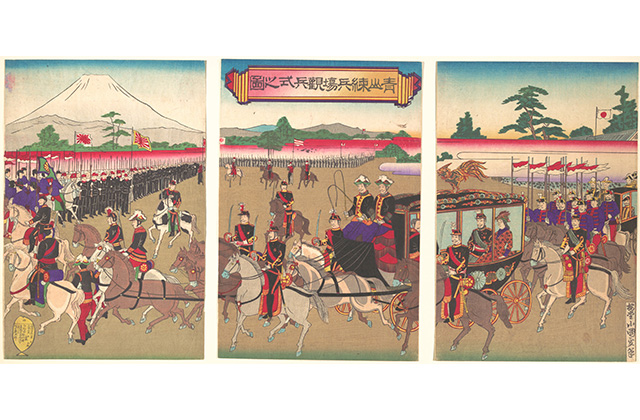

The Meiji era is known as the “age of enlightenment” due to the infiltration of Western practices in commerce and industry. Several domestic reforms like mandatory military service, as well as compulsory education for the purpose of imparting industrial skills and, of course, indoctrination, were also set up during this time.

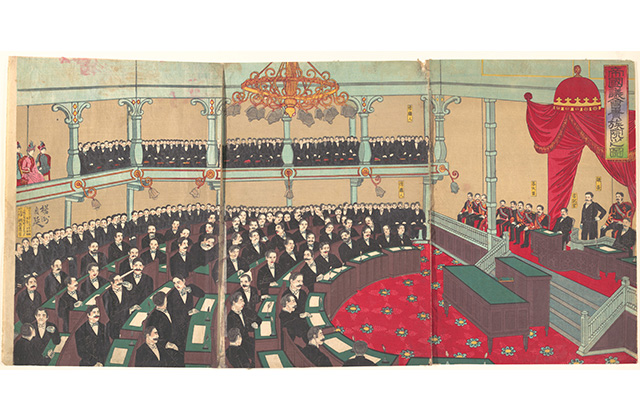

Lords and samurai lost their high status, resulting in more social equality, and previously looked-down-upon merchants began to receive respect. Government-wise, a parliament which was held accountable to the emperor, was established.

Budding trade with the US and other Western countries aided in Japan’s economic success, as did engaging in war with Russia.

Taisho “Democracy” Era: 1912-1926

During the Taisho era, poor health of the emperor lead to fewer public appearances and a general loss of power to the Diet. In light of this imperialist remission, democracy bloomed, especially in the area of women’s rights, and labor unions began forming. These actions lead to more egalitarian attitudes which were often expressed in music, causing this era to be referred to as Japan’s Roaring 20’s!

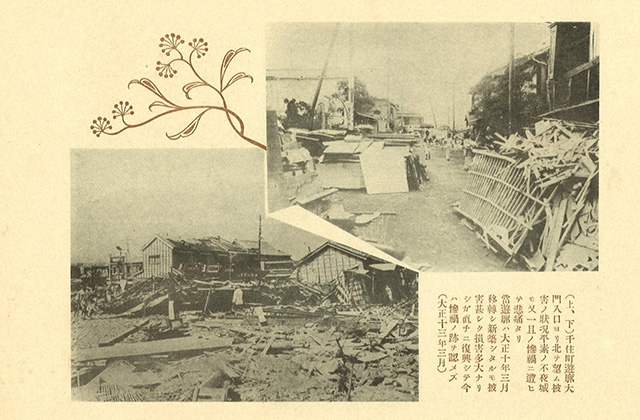

The Great Kanto Earthquake and resulting riots, however, reverted these social advances, and attacks against ethnic groups like Koreans and Chinese were common.

On the world front, the achievement of international status via a naval treaty with Great Britain and the US was celebrated, but soon overshadowed by economic hardship. Subsequently, Japan was shocked by the League of Nations’ refusal to accept its resolution to the Covenant to forbid discrimination based on race. Eventually, there was a return to imperialist attitudes due to, or for the sake of, military efforts in Manchuria, Korea, and Taiwan.

Showa “Japanese Glory” Era: 1926-1989

Occupation of Taiwan, Korea, Manchuria and even parts of Siberia, as well as Vietnam and other Southeast Asian countries, had Japan rearing its imperialist head and led to its eventual alignment with the Axis powers. Many surrounding countries were affected by Japan’s aggressive military actions during this era of ethnocentrism.

Overt promotion of nationalism can be seen in state-sponsored posters and advertisements, especially in the publication Shashin Shuuho. Daily participation in nationally-aired radio gymnastic exercises was encouraged through these ads, and magazine covers with images of military prowess (abandoned enemy helmets, up-close shots of warships) made false proclamations of success and stability on the front line. (The photo on the right was taken in 1964 after the war.)

Coup attempts like the 2-26 Incident in 1936, by young officers in the Imperial Japanese Army, represent the overall feeling of social instability and discord. Domestic reforms like the strengthening of already established neighborhood associations (which still exist today!) were used for micro-management purposes, and various groups forcefully promoted ultranationalist ideas.

After WWII, Japan was occupied by a foreign country for the first and only time in its history. During the seven-year occupation, the emperor’s power was deflated considerably and democracy returned. Like a good Godzilla, Japan rose from the horrible destruction of war, and was chosen to host the 1964 Olympics, impressing everyone with a show of fantastic technological advances, like the bullet-train.

Other policies were developed, too, with a focus on human rights that remains strong today. Efforts toward international cooperation and the promotion of peace were at the core of post-war Japan’s attitude. This amiable approach was rewarded towards the end of the Showa period with the economic miracle of the “Bubble.”

Despite the horrors inflicted by and upon each other during WWII, this era is representative of the resilience of human beings to rebuild and move on. As a result, it holds a romantic nostalgia for many people. Television shows that take place during this time period are extremely popular today. There are even entire museums dedicated to providing a hands-on glimpse of Showa daily life: https://ota-tokyo.com/showa-no-kurashi-museum-museum-of-life-in-the-showa-era/

Heisei “The Lost Years” Era: 1989-2019

With its peaceful name (the Chinese characters chosen for this era mean “peace everywhere”), the Heisei Era is becoming known for its relative stagnation and a tendency to allow political policies to be shaped by public opinion. It is a time (not only in Japan, but worldwide, in the Age of Social Media) when celebrities on talk shows and Twitter, rather than actual, serious economic discussion, seem to have more influence on public opinion. Peace everywhere is an honorable goal, but a general ennui seems to have surfaced with the absence of something to fight for/live for/die for.

The popping of the “Bubble” and its subsequent recession, have also earned this era the title, “The Lost Years,” because there was very little, and sometimes even negative, economic growth. Japan’s international leadership position, too, has been usurped by the rise of other Asian economic powers like China, Korea, Indonesia, and Hong Kong.

National disasters like the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, the resulting tsunami and the nuclear power plant accident in Fukushima, forced the Japanese government into the international limelight. Although extensive efforts, both physical and financial are still going on, editorials criticizing Japan’s post-disaster response and social pressure to reform energy sources continue to be published even today. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2019/03/11/editorials/eight-years-3-11-disasters/#.XLaN_Oj7TIU

The Reiwa Era: 2019-

Japan’s newest era, not Stiff Upper Lip, as the author originally supposed, but Reiwa, takes its characters from an ancient Japanese poem (a new tradition, as characters are usually chosen from Chinese classics). Rei usually means “order” and wa is known as the character for “peace” or “harmony.” Combined, these characters have led some to suspect imperialist undertones, but those claims have been denounced. When asked about the meaning of the name, Prime Minister Abe was quoted as saying, “Culture is born through the beauty of people caring for one another.” Since then, both an official English name “Beautiful Harmony,” and a Japanese sign language sign reflecting its meaning have been presented.

Speculations about what this era will bring abound, but the general feel is one of hope and renewal, where Japanese culture is preserved and tactfully passed on to a receptive next generation, as well as being shared and appreciated on a global level.