TRG Info and Advice

The History of Japanese Traditional Music

When you hear the words, “Japanese music,” what comes to mind? Sukiyaki? Babymetal? Hatsune Miku? Kodo? Perfume? Anime and video game soundtracks?

We are surrounded by a vast array of music in the modern world; in shops and cafes, on TV and in films, not to mention personal stereos, computer games and others. Among these, however, Japanese traditional music is almost non-existent. Here we will navigate you through the history of Japanese music, with a focus on traditional genres, and introduce you to some conventional music.

Most traditional Japanese music, with a handful of exceptions, developed from a base of narrative and lyrical vocalizations that related stories or poems, and were accompanied by instruments.

6th to 8th centuries

Political and cultural exchanges with China and the Korean Peninsula intensified from the 6th to 8th centuries. Along with Buddhism, a variety of music was brought to Japan (including Buddhist music and musical instruments), from as far as Thailand, Vietnam and the Bohai State, as well as Korea and China. Among them, Chinese court music, which was mostly presented with dancing, made a significant impact on music in Japan. Until that time, folk songs had been sung with dancing and musical accompaniment during Shinto rituals, ceremonies and functions at the regional level, as well as for the purpose of passing down history and important information from one generation to the next. As the governing power became centralized, local music was brought to the capital and adopted into court music.

Before long, a governmental music bureau was established with two departments: one dedicated to native music and the other to foreign music. It supervised court music and dance (the gagaku ensemble), and professional musicians who performed music and dance in the imperial court. The profession was hereditary, and its repertoire and traditions have been passed down from father to son for centuries. There are some families who carry on this tradition even today.

The general public was not exposed to foreign music. It was played mainly for the imperial families and court nobles by a small number of experts during observances held at the imperial court and temples. According to records, the diversity of foreign music in Japan reached a high point in 752, at the massive bronze Buddha statue’s eye-opening ceremony at Todaiji Temple in Nara. A great variety of music was presented along with monks chanting sutra. The Shosoin Repository at Todaiji Temple still houses over 70 examples of 18 kinds of musical instruments from that time, some of which are no longer in existence today.

9th–12th centuries

From the 9th to the 12th centuries, music gradually began to take root in the private lives of nobles: music and dance were performed during private parties by nobles themselves, and it became an important art form that the upper-classes were expected to learn. Around this time, the koto, or so (long zither) began to be used independently, apart from the ensembles performed during rituals in the imperial court and temples, and religious vocal music (the chanting of Buddhist sutras) went into full swing. The Shomyo Buddhist chant originally brought to Japan in Sanskrit and Chinese began to be transposed to fit with the intonation of the Japanese language. That composition method became significant in the music scene, and was used when heikyoku (the music played on the heike biwa as accompaniment to the recitation of The Tale of Heike), and joruri (a chanted recitative) developed into a music genre called katarimono (narrative music).

Shomyo http://www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/dglib/contents/learn/edc8/deao/wasan/index.html

After the Tang Dynasty fell and the imperial envoys to Tang were abolished at the beginning of the 10th century, contact with foreign culture diminished. This lead to a variety of music being reorganized and gagaku to be nurtured in an indigenous way. Thus, distinctively Japanese versions of gagaku began to be composed, and popular songs emerged from this form of music, too.

Gagaku is a small orchestra consisting of strings and wind instruments accompanied by dance. Gagaku has waxed and waned through the millennium keeping nearly with the same style, including costumes, instruments and contents. Today, gagaku is transmitted by many groups, including the Imperial Palace Music Department, and performed during court observances, banquets and concerts.

Gagaku (Saibara) http://www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/dglib/contents/learn/edc8/deao/saibara/index.html

Popular song (Imayo) http://www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/dglib/contents/learn/edc8/deao/imayo/index.html

13th century

In the 13th century, samurai replaced court nobles as the managing government, and biwahoshi, musicians who narrated stories about war with biwa accompaniment, appeared. This music is called heikyoku. It is a type of narrative biwa music which relates the prosperity and decline of the Heike family, and was performed by monks who were blind, members of a guild called Todo. Later, the musicians of Todo actively incorporated the koto and shamisen (a three-stringed lute), bringing these instruments to the limelight for composition and performance.

Heikyoku http://www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/dglib/contents/learn/edc8/deao/heikebiwa/index.html

14th–16th centuries

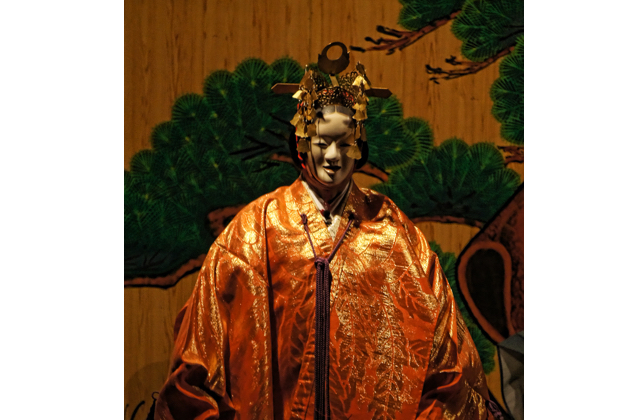

Sarugaku, mimicry with musical accompaniment, was brought to a level of perfection and sophisticated Noh made its appearance, thanks to the patronage of the shogun. In the process of refinement, songs and dance were added to the art of mimicking and performances were minimized and stylized, while the staging space was simplified. Noh is performed with song and the musical accompaniment of a flute (nohkan), a small hand drum (kotsuzumi), a large hand drum (okawa) and a drum (taiko). The music is called yokyoku.

Noh (Aoi no Ue) http://www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/dglib/contents/learn/edc14/aoinoue/kansyou/point/sono3.html

Yokyoku (Makiginu) http://www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/dglib/contents/learn/edc8/deao/youkyoku/index.html

During this period of time, the three-stringed sanshin emerged from Ryukyu (currently Okinawa), and later transformed into the shamisen, made with the skin of dogs or cats instead of snakes. It was the biwa players who saw potential in this musical instrument, and use of the shamisen soon spread nationwide. Later, in the Edo Period (17th–19th centuries), it became an essential instrument for song accompaniment (jiuta).

Jiuta (Sode no Tsuyu) http://www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/dglib/contents/learn/edc8/deao/jiuta/index.html

Mid-16th century

In the middle of the 16th century, guns and Christianity were brought to Japan, and church music was introduced by the missionaries of the Society of Jesus. This was the first European-style music that Japanese people had ever heard. By the late 16th century, the chorus of Gregorian chants and performances of Western musical instruments could be heard in Oita, which was the center of the Society of Jesus missionary. Music was even taught at seminaries for children of the high-ranking samurai. Church music performances were, however, limited to churches for Japanese Christians, and before this style of music took root in the public, Christianity and everything related to it were completely banned (in some places, however, people kept their faith and have covertly passed down church songs for generations).

Even as wars and confusion in society continued, the social and economic status of the common people rose, inspiring the development of folk performing arts such as Odori Nenbutsu (a dance performed while reciting the name: Amida Buddha). Cultural exchanges beyond social class became active, and the musical genre of kouta became popular among the common people.

Kouta (Nanatsugo) http://www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/dglib/contents/learn/edc8/deao/chusei/index.html

17th–19th centuries

After the establishment of the Tokugawa Shogunate, an extended period of peace empowered the common people. Distinctively Japanese culture blossomed, because the Shogunate’s policy was to close the doors on the rest of the world. Music was composed and performed in big cities such as Edo (modern-day Tokyo) and Osaka, and the general public proved to be a responsive audience.

One of the most popular kinds of music involved the shamisen. This instrument, brought to Japan in the 16th century, quickly and widely spread among the common people, and played a major role in the popular music of the time.

During the Edo Period (17th-19th centuries), the music that people enjoyed was different depending on their social class: Gagaku was for court nobles and Noh was for the samurai class. The Shogunate had a bureau that supervised Todo and promoted performances by artists who were seeing-impaired, and who also made up the great majority of jiuta and koto musicians. Shakuhachi (an end-blown bamboo flute) was designated a religious musical instrument by the Shogunate and only priests of the Fukeshu Sect of Buddhism were allowed to play it.

Shakuhachi music (Shika no Tone) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sQdzKhJHqe4

After the 17th century, narration with shamisen accompaniment and puppet plays became integrated, fascinating people with ningyo joruri (puppet theater). Out of several joruri schools, one specifically had a strong influence on Kabuki dance music.

Ningyo Joruri (Bunraku) Heike Nyogo no Shima http://www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/dglib/contents/learn/edc8/deao/gidayu/index.html

Kabuki, too, appeared and became popular during this period of time. Kabuki Theatre was originally a dance performance with singing, but transformed into a theatrical art in the late 17th century. A florid and lilting style of music found in Kabuki plays called nagauta (songs with shamisen accompaniment), developed, too.

Kabuki (Musume Dojoji)

http://www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/dglib/contents/learn/edc11/sakuhin/enmoku/p7/b.html

Nagauta (Kyokanoko Musume Dojoji)

http://www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/dglib/contents/learn/edc8/deao/nagauta/index.html

Also around the 17th century, use of the koto expanded. While the accompaniment of songs was performed mainly by shamisen until around that time, koto began to be played along with the jiuta songs as well. A genius koto player named Yatsuhashi Kengyo improved the instrument so that it could produce louder sounds in order to be played solo, and began changing the positions of bridges to play different scales. Thus, he built the foundation for today’s koto music.

Koto music (Kumoi no Kyoku) http://www2.ntj.jac.go.jp/dglib/contents/learn/edc8/deao/ikuta/index.html

Late 19th century

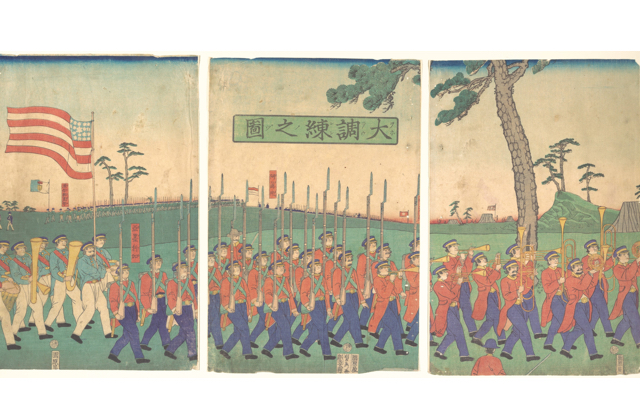

When the U. S. Commodore Perry visited Japan to negotiate the opening of the country, a military band accompanied him on his expedition, and it offered a window to Western music for Japanese people. In efforts to counter the great powers, Western-style military groups were organized in feudal domains around Japan and military music using drums and bugles was introduced, too. So, by the time of the opening of the country, there was already a foundation of Western-style music. Music began to be composed and performed using European methodology among the military bands and musicians from the Imperial Palace Music Department.

Also around this time in the late 19th century, the national anthem “Kimigayo” was created. Music education was started in elementary and middle schools to teach shoka (how to sing songs with instrumental accompaniment) and organs were brought in. Music teachers were invited from the US, and many songbooks were published. Among others, songs such as Hotaru no Hikari (light of fireflies) were created using the melody of foreign folk songs like “Auld Lang Sine.” This melody is popular even today and is often heard when shops are closing for the night, at the end of sporting events such as the High School Baseball Summer Championships, and on the end-of-the-year “song battle” TV program, Kohaku Utagassen.

The reason for this song’s popularity is because the tune is similar to the traditional pentatonic scale most familiar to the Japanese ear. This scale consisting of five tones continued to have an influence on Japanese composers even after the late 19th century. At first, the Western-style music composed by the Japanese people was slow in tempo like gagaku, but after the First Sino-Japanese War, skip-like lilts became prevalent.

Hotaru no Hikari https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=brUWAlQsWMg

Early 20th century

Many songs were written and composed to fit with the intonation of the Japanese spoken language, for example, Usagi to Kame (rabbits and turtles), Hatopoppo (doves) and Oshogatsu (New Year’s Day). Around 1900, people eagerly took in Western music and a great number of songs and instrumental pieces were composed at that time. Many songs were sung at schools and preschools, and education became the incubator of Western-style Japanese music.

Hatopoppo composed by Rentaro Taki https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hlZdpLe6YtQ

Military bands, as well as music groups organized by former members of military bands, also provided opportunities for people to become more familiar with Western-style music through regular concerts and music tours. Some people were inspired by these concerts to become professional musicians.

The Taisho Period (1912–1925) saw the emergence of popular songs because people began to have record players. Radios also played a significant role in spreading a variety of music among the common people. As people gathered in large cities for more job opportunities from local regions, local folk songs also flew into cities, and that led to the folk song boom. Opera and orchestral music were performed and enjoyed as well.

Kachusha no Uta (Katyusha’s song) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TiMpE83f8GM

In the traditional music scene, Michio Miyagi, a koto player and composer, made a great contribution. He adapted Western music methodology to compose and perform music for the koto and other traditional Japanese instruments, and invented the 17-string koto (koto traditionally has thirteen strings) in order to play lower sounds. He began performing Western music using Japanese instruments, and thus forged a new form of koto art that suited contemporary tastes, while maintaining traditions.

17-string Koto* performance (Seoto) *Koto on the right https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LF3bM0X_xDY

After the mid-20th century

After World War II, a movement to revive Japanese classical music began and traditional Japanese music was reappraised. Brand-new Noh plays were created, and conventional musicians expanded the potential of traditional instruments by actively applying Western music methods. Toru Takemitsu’s orchestra piece, “November Steps,” featured biwa and shakuhachi solos, drawing attention abroad to these instruments after its sensational world debut in New York in 1967

A hundred years after the first encounter with Western music, Japanese composers, including Akira Ifukube, Toshiro Mayuzumi and Maki Ishii, as well as Toru Takemitsu, became known worldwide. Isao Tomita became the pioneer of synthesizer music and inspired the world, too.

What is happening to traditional music and people who play it? Traditional music is now almost ignored by the majority of Japanese people. The number of people who are familiar with the piano and the guitar is probably way more than those who are with koto and shamisen. Music education at schools is centered on European classical music after the mid-18th century rather than Japanese music, and musical instruments commonly seen at schools are recorders, keyboard harmonicas, pianos and organs. It is only recently, in 2002, that it became mandatory for middle schoolers to learn to play at least one Japanese traditional instrument such as the koto, the bamboo flute or the shamisen in music class. In reality, however, students often end up just briefly listening to a few traditional music pieces due to the lack of teachers who know how to play and/or teach traditional musical instruments, and funds to provide students with enough instruments.

Younger generations of traditional instrument players are pushing themselves hard to reach a wider audience by playing popular tunes, or pieces composed or arranged in Western music styles. They are going solo, putting together ensembles of traditional instruments, or playing with Western instruments such as the electric guitar, drums and the piano, in order to make themselves more accessible to modern tastes while still honoring their heritage. However, whether these efforts will be fruitful without being short-lived booms and whether traditional music will rank with Western-style music in Japan in the future is still in doubt. That said, Japanese people tend to be more familiar with Western music than traditional Japanese music, so conventional instruments used to play Western-style music could be a hook for creating interest in traditional music. Fusion with the West and future innovations could be standard, or even traditional, 400 years from now!

Bad Apple!! Performed by an ensemble https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dx76YPgZviE

Oriental Journey by AUN J Orchestra https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rzDnHiT_-ao

Senbonzakura by Wagakki Band https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K_xTet06SUo&list=RDbKQp5zHMwC8&index=6

Stairway to Heaven (Led Zeppelin) performed by two sets of Koto and Shakuhachi https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nZPnt4tKGdU

Beat It (Michael Jackson) performed by Otsuzumi, Nohkan, Kotsuzumi, Taiko, bass and guitar https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DFQ4DJuwJwA