TRG Info and Advice

The Abundant World of Seaweed

Have you ever eaten seaweed? If you have, what did you think about it? Thin, bright green ribbons of wakame in your miso soup, tiny green flakes on your potato chips, maybe you didn’t even realize what you were eating! How about that black sheet wrapped around sushi or onigiri (rice balls)? It is one of the most common seaweeds eaten in Japan: nori.

Japan, with seas on all sides, is, consequently, a country surrounded by seaweed. In Japanese waters, where warm and cold currents meet, many coastlines consist of rocky shores, creating the perfect growing environment for over 1,500 varieties of seaweed.

Seaweed-eating culture is not exclusive to Japan, but is characterized (in Japan, as well as in China and Korea) by the consumption of fresh or cooked seaweed on a daily basis, much like vegetables. In Japanese meals, specifically, more than twenty species are used.

The History of Seaweed Use

As coastal people around the world do, the Japanese have been utilizing seaweed since prehistoric times, and traces of seaweed have even been discovered in shell mounds (ancient garbage dumps). It is not a stretch to imagine people naturally eating seaweed along with fish and shellfish. In the past, however, it is thought that seaweed was consumed mainly for the purpose of taking in salt.

In books and on wooden tablets with writing from the late 7th century towards the 8th century, it is possible to identify the names of different kinds of seaweed, which are still eaten today, such as wakame, hijiki, and aonori. People used various types of seaweed to pay taxes to the Imperial Court, and seaweed was also used as an offering at shrines. At markets held in the imperial capitals of Heijokyo and Heiankyo, there were shops that sold seaweed, tokoroten (seaweed jelly), and other seaweed goods. In an anthology of ancient Japanese poetry called “Manyoshu,” there are over a hundred poems depicting scenes of both salt-making (by repeatedly pouring seawater over seaweed and sun-drying it), and of seaweed collecting for food. These discoveries suggest that seaweed was an important part of everyday life.

As Buddhism spread, seaweed began playing an important role in shojin ryori (Buddhist vegetarian cuisine), as well as being processed as an ingredient used in making confectioneries. In the Kamakura Period (1185-1333), beautifully prepared, aromatic and sophisticated dishes made using seaweed appeared. In the Sengoku Period (1491-1573), seaweed was an essential food item used as both a portable food and a stockpile. In the Edo Period (1603-1867), seaweed was used for a famine food. In addition, many seaweed products developed and local, specialty seaweed dishes were produced in each region.

In this way, seaweed became a staple food in the Japanese diet, and also came to be used as a treat that appeared at feasts on special occasions. Over the years, experiences and knowledge of seaweed consumption accumulated, and that led to the emersion of regionally different cooking and preservation methods.

Recently, however, younger generations eat seaweed less often than before, and some of the traditional, regional seaweed cuisines are on the verge of disappearing.

Please note: Hand harvesting of seaweed from the foreshore or seabed may require a license from the local fishermen’s cooperative association.

Nutrient-rich Sea “Vegetables”

Seaweed is rather mild-tasting, and might not be the main dish. It is, however, rich in vitamins, vegetable protein, minerals such as calcium, and fibers. Thus, the nutritional value of sea “vegetables” is attracting more attention than ever.

・ Dietary Fibers

Seaweed contains high levels of both soluble and insoluble dietary fibers. The distinctive sliminess comes from insoluble dietary fibers, including alginic acid and fucoidan.

・Protein (Amino Acids)

Seaweed has higher levels of good quality protein than soybeans. Wakame, especially, contains the total amount of all essential amino acids that we need.

・Vitamins

Containing Vitamin A, B-complex vitamins, Vitamin C and Vitamin E, seaweed, in fact, has higher levels of some vitamins than vegetables.

・Minerals

Our bodies need more than 90 kinds of minerals. While plants from the ground contain about 60 varieties of these, seaweed has all of the necessary minerals, and is especially high in calcium, potassium, and magnesium. Furthermore, minerals contained in seaweed are easy to digest.

・Zero-calorie

Seaweed itself is a zero-calorie food, so it is possible to eat a lot of it without putting on weight. It is important, however, to have a well-balanced diet.

Various Ways to Use Seaweed

As some of you might be aware, seaweed is used, as is, in ways apart from food. As the varieties and characteristics of seaweed were discovered, so have a wide range of uses, including ingredients for glue, fertilizer, and chemical products, among others. Here are some examples.

・Ice Cream: Varieties of Okirinsai (E.striatum Schmitz) are used when making ice cream. Sodium alginate contained in seaweed is used to stabilize the dairy-based solutions. It also helps maintain the stability of the frozen structure by keeping the air content in, making that soft, melt-in-your-mouth texture. Carrageenan, contained in the red algae species, is used as an emulsifier.

・Ham: Carrageenan, contained in okirinsai (E.striatum Schmitz) is added to produce elasticity.

・Cosmetics: Substances derived from okirinsai (E.striatum Schmitz) varieties are added to create smoothness and a thicker texture.

・Medicine: Kainic acid derived from moakuri (digenea) is used for anthelmintic medicine (used to fight parasites).

・Toothpaste: Substances derived from okirinsai (E.striatum Schmitz) varieties are added to make the paste thicker.

・Fire Extinguishers: Carrageenan, derived from okirinsai (E.striatum Schmitz) varieties, helps strengthen the foam.

・Kimono: The textiles produced in Amami Oshima Island, “Oshima Tsumugi,” is woven with threads made using funori (Endocladiaceae varieties) seaweed.

・Fodder: Powdered seaweed is fed to fish, chicken, cows and pigs.

・Fertilizer: Since ancient times, seaweed has been used as a fertilizer all over the world. Powdery or liquid fertilizers are considered to improve the quality and yield of crops.

Seaweed Varieties

*Green Algae

Ulva Pertusa Kjellman

Ana-aosa (Aosa) [Ulva pertusa Kjellman]: Wild-harvested in summer, ana-aosa is then dried, powdered and made into furikake rice seasonings. As the Ana-aosa aroma stays even when it is heated, it is often used for okonomiyaki, takoyaki and rice crackers.

Kubirezuta (Umibudo) [Caulerpa lentillifera]

Foraged in July and August, Kubirezuta is also known as umibudo (sea grapes), and is mainly consumed in Okinawa. Featuring a popping texture, it is usually used for salads.

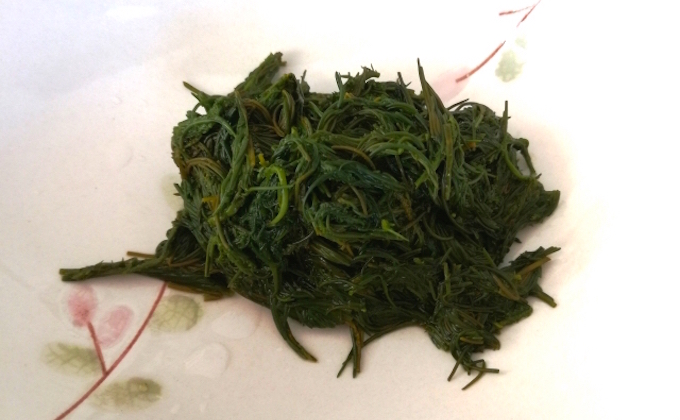

Suji-aonori (Enteromorpha prolifera (Müller) J.Agardh)

Farmed in brackish water areas, suji-aonori is harvested from December through March. The most famous suji-aonori variety is foraged in the River Shimanto in Kochi. Suji-aonori tastes and smells best among the edible varieties of aonori seaweed. It is often served in soup dishes or as tempura, but is flavorful when lightly seared and sprinkled over white rice, too. The price of suji-aonori is sometimes three times more expensive than ana-aosa.

Hitoegusa (Monostroma nitidum)

Harvested from February to April. In Japan, most hitoegusa is farmed off the coast south of Central Honshu, in the Pacific Ocean and southern parts of the Sea of Japan. Hitoegusa is an ingredient of aonori (green laver powder) and tsukudani (nori boiled down with soy sauce and mirin). It is also made into miso soup and tempura.

Miru (Codium fragile (Suringar) Hariot)

Growing off the coast of Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu, miru is harvested from the end of July through late August. In Japanese, miru is written 海松 (sea pine tree), which reads miru. It is usually made into a vinegared dish or served with vinegared miso (bean paste). Miru has been consumed since ancient times, and in the Nara Period, people used it to pay their taxes. Nowadays, it is not eaten as often as before.

*Brown Algae

Konbu (Saccharina spp)

Harvested in Tohoku and Hokkaido, Konbu is one of the most common seaweeds for Japanese people this millennia. Konbu is often boiled down with soy sauce and mirin to make tsukudani. It is also processed into tororo (shaved, dried konbu), and is an essential ingredient of soup stock in Japanese cuisine.

Wakame (Undaria pinnatifida (Harvey) Suringar)

Wakame can be found from off the coast south of Hokkaido to Kyushu, and is harvested from February through April. Harvested wakame is preserved by drying and salting. Wakame is eaten in various ways: in miso soup, vinegared dishes, soup, sashimi, and salads, among others. The bottom part of wakame, stipes with folds, is called mekabu. When chopped, it becomes sticky. Mekabu tastes delicious with wasabi and soy sauce.

Hijiki (Sargassum fusiforme (Harvey) Setchell)

Hijiki can be found in the areas south of Hokkaido to the Nansei Islands, and is wild-harvested from March through May. Hijiki has been being eaten since ancient times, along with konbu and wakame. It is usually dried for preservation and then reconstituted in water before cooking. Hijiki is used in simmered dishes, mixed with rice, and in salads, among others. Depending on the region, it is sometimes slowly boiled with other kinds of seaweed such as arame and kajime first, so the hijiki can soak up their delicious flavors. It is then dried before shipping. During this process, the color of hijiki becomes black. Foreign authorities have recommended not eating hijiki, stating that it contains arsenic. However, arsenic is soluble and can be avoided if you put dried hijiki in plenty of water for longer than thirty minutes. The water used to soak the hijiki must be disposed of, of course. After 30 minutes of soaking, rinse the hijiki with running water two or three times, and wring it lightly before using.

Matsumo (Analipus japonicus (Harvey) Wynne)

Wild-harvested in a comparatively short period of time (April through May), Matsumo is eaten mainly in the Sanriku region of Tohoku. It has a distinct texture and tastes delicious. Matsumo is usually used for vinegared dishes, miso soup and clear soup.

Habanori (Petalonia binghamiae (J.Agardh) Vinogradova)

Habanori is collected from winter to spring all over Japan. Dried habanori is an ingredient of miso soup, and is also eaten, seared and sprinkled over rice. In some parts of Chiba Prefecture, habanori is an essential ingredient of zouni soup in the New Year. Dried habanori sheets are premium foodstuff.

Akamoku (aka Gibasa / Nagamo) [Sargassum horneri (Turner) C.Agardh]

Akamoku is wild-harvested from February through April in the seas south of Honshu. In the coastal areas along the Sea of Japan, such as Shimane and Sado Island, a similar kind of seaweed, hondawara (Sargassum fulvellum (Turner) C.Agardh), is also consumed. When akamoku is chopped, it becomes sticky. It is usually eaten with soba (buckwheat) noodles or yam potatoes.

Arame (Eisenia bicyclis (Kjellman) Setchell)

Arame is foraged from July through September, off the coast of central and northern Honshu in the Pacific Ocean and in the north of Kyushu. Usually cut into strips, arame is used for simmered dishes and miso soup, and is also made into arame rolls as is. Alginic acid extract derived from arame is used for food additives (stabilizer). There is a very similar kind of seaweed called kajime (Ecklonia cava Kjellman), and in some areas, the two names are often mixed up: kajime is called arame and vice versa.

*Red Algae

Amanori varieties (Pyropia spp)

The amanori species is cultivated in the bays, or just off the coast, all over Japan, from Hokkaido to Kagoshima. Amanori variety seaweed is an ingredient of nori, which is used when making sushi rolls and onigiri (rice balls). Amanori is an essential seaweed for festivities and special occasions.

Makusa (Tengusa) [Gelidium elegans Kützing]

Makusa is harvested May – June in all parts of Japan. The one harvested in the areas along the Pacific Ocean is considered to be high quality. Makusa is usually processed and made into agar and tokoroten jelly. In Ishikawa Prefecture, there are special, local dishes called Suizen and Ebisu. Suizen is made by kneading Makusa with rice powder and coagulating the mixture. Ebisu is made by mixing Makusa with eggs and heating the mixture until coagulated. Suizen is usually served at Buddhism ceremonies, whereas ebisu is served on celebratory occasions such as the New Year.

Funori (Endocladiaceae varieties)

Funori is harvested in winter and spring in Kyushu, Shikoku and the Sanriku region in Tohoku. Funori is dried before shipping. The reconstituted and drained funori is then prepared into vinegared dishes and miso soup. In Niigata, funori is added to soba (buckwheat) noodles. It is also used for industrial products.

Umizomen (Nagaramo) [Namalion vermiculare Suringar]

Umizomen is wild-harvested from May through July in the northern parts of Kyushu, San’in, and the Noto Peninsula. Umizomen is usually made into vinegared dishes and miso soup.

Tosakanori (Meristotheca papulosa (Montagne) J. Agardh)

Tosakanori can be found off the coast of the Pacific Ocean, Seto Inland Sea, and the west coast of Kyushu. When fresh, the color of Tosakanori is bright red, but it turns green when hot water is poured over it. If it is then soaked in water, the color turns white. Tosakanori is used in seaweed salads to add color.

Egonori (Campylaephora hypnaeoides J.Agardh)

Akaba Gin’nanso is harvested from January through March in Hokkaido, and in the northern areas of Tohoku along the Pacific Ocean. It is served in miso soup, or as tempura and other dishes. In Hachinohe City, Aomori, there is a very rare and traditional local food called Akahatamochi, which is made by pounding steamed Akaba Gin’nanso.

Kirinsai (Eucheuma muricatum (Gmelin) W. v. Bosse)

Kirinsai can be found in the southern parts of Japan, and it is harvested in spring. Kirinsai is usually processed to extract Carrageenan. Recently, Kochi Prefecture is making efforts to cultivate kirinsai, aiming to make the seaweed a local specialty. In Okinawa Prefecture, it is called Suunaa. Kirinsai is usually used for salads, miso soup, and vinegared dishes, among others.

Ogonori (Gracilaria vermiculophylla (Ohmi) Papenfuss)

When it is blanched, Ogonori turns bright green. That is why it is used for a condiment of sashimi. It is also used as an ingredient for soup dishes.

Igisu (Ceramium kondoi Yendo)

Igisu is foraged in the vast area stretching from Hokkaido to Kyushu, mainly in July and August. Igisu is usually used for agar or as a sashimi garnish. In Ehime Prefecture, Igisu and fresh soy powder is mixed with dashi stock and heated until Igisu is dissolved. The coagulated, agar-like food is called Igisu Dofu (tofu), a local specialty served during Obon (Obon is the time when the spirits of the ancestors return home for a short visit) and at Buddhist ceremonies.

Tsunomata (Chondrus ocellatus Holmes)

Tsunomata is harvested in Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu. It is consumed mainly in Chiba and Ibaraki. Tsunomata is boiled until dissolved and coagulated, and the coagulated jelly is eaten with vinegared miso, or Japanese mustard and soy sauce.

Matsunori (Polyopes affinis (Harvey) Kawaguchi et Wang)

Matsunori is harvested in Hokkaido, Honshu and Kyushu. It is usually used for vinegared or dressed dishes.

Mukadenori (Grateloupia asiatica Kawaguchi et Wang)

Mukadenori can be found from winter to spring in all parts of Japan. It is usually prepared into salad, used in konnyaku-like food, and tsukudani (boiled down with soy sauce and mirin).

Akaba Gin’nanso (Mazzaella japonica (Mikami) Hommersand)

Akaba Gin’nanso is harvested from January through March in Hokkaido, and in the northern areas of Tohoku along the Pacific Ocean. It is served in miso soup, or as tempura and other dishes. In Hachinohe City, Aomori, there is a very rare and traditional local food called Akahatamochi, which is made by pounding steamed Akaba Gin’nanso.