TRG Info and Advice

Kimonos Now and Then, Part 2

Part Two: A Short History of Kimonos

In the beginning, Japanese people wore simple two piece garments. With the invention of the straight-line-cut method in the Heian period (794-1192), however, dressmakers figured out how to cut a single, 12-13 meter long piece of fabric into eight pieces (sleeves, body, collar) and this lead to the appearance of the kimono. This method made it easy to replace a piece or panel of fabric if it became damaged or faded. In olden times, kimonos were even disassembled in order to be washed, then sewn back together. Their boxy shape also made for easy folding and storage.

Another benefit of this new style of dress was that kimono makers no longer needed to worry about the wearer’s body type, as the nature of kimonos allowed for easy adjustments to fit any shape. They could also be layered and the fabrics chosen to accommodate various temperatures: more layers of thicker fabrics like wool in the colder months, and fewer layers of cotton or linen in warm weather.

Kimonos were originally divided into kosode or osode (small sleeve holes and big sleeve holes), with kosode eventually winning out as the garment of choice. The word kimono means “worn thing” and became the one used to describe what we identify as kimonos in the Meiji era, after the opening of Japan to the western world, to distinguish Japanese-style clothing from Western.

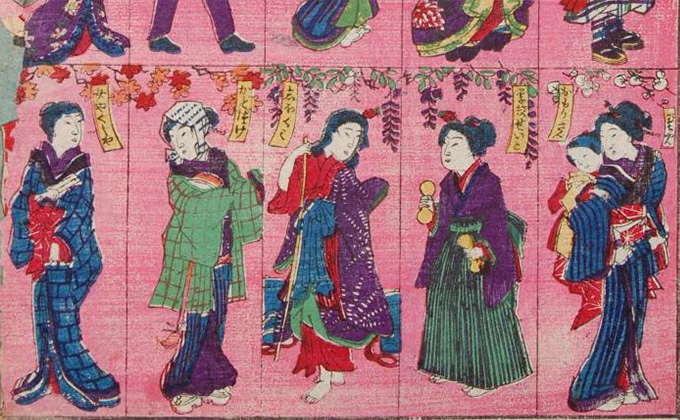

During the Kamakura period (1192-1338) colorful kimonos were the height of fashion. Both men and women could be found in brightly colored kimonos with decorative motifs. These patterns were highly significant; indicating age, gender, wealth and taste. Next followed the artistic Muromachi period (1338-1573), with a focus on tea ceremony and Noh Theater. Towards the end of this peaceful period, however, revolutions and uprisings lead to civil wars, with warriors donning brightly colored kimonos that represented their samurai leaders. The need to supply samurais with military and domestic materials stimulated the merchant classes, who created commercial centers and associations.

Merchants, therefore, found themselves with extra cash on their hands, and many chose to spend it on new and novel kimono patterns and colors. With the rise of the merchant and samurai classes during the Momoyama period, the ruling class felt the need to assert control via rules regarding the colors and materials of the kimono. They created laws stating what colors should be worn by certain ranks, what materials could be worn by certain classes, and even who was allowed to give whom a kimono as a gift!

Next came the Edo period (1603-1868) with its Tokugawa clan feuds. Samurais wore their domain’s colors and patterns like a military uniform, with stiffly starched kamishimo (a sleeveless, vest-like garment) and hakama worn over the kimono. Red was forbidden during this period, but subversives acted-out by wearing red sashes or undergarments, and flashing them (chiramise) to passersby. (Chiramise is the act of providing a quick glimpse of something without the intention of actually having it be seen, and is still considered a tool of sexuality.) Also during this time, the kimono-making process improved greatly and kimonos, themselves, gained value, becoming family heirlooms to be preserved and passed on from generation to generation. One type of woven fabric used for kimonos is called yuki-tsumugi, made in the city of Yuki, Ibaraki Prefecture, and this fabric is said to be so sturdy it lasts 300 years.

The Meiji period (1868-1912) is most known for the end of Japan’s self-imposed isolation and the introduction of Western influence and clothing. Army and government officials, especially, were required by law to wear Western-style uniforms and suits. Common people were required to wear kimonos with their family crests for special events, so as to have their background identified easily. But during the following Taisho era (1912-1926), moga (modern girls) experimented with “daring” kimono color combinations.

The Meiji period (1868-1912) is most known for the end of Japan’s self-imposed isolation and the introduction of Western influence and clothing. Army and government officials, especially, were required by law to wear Western-style uniforms and suits. Common people were required to wear kimonos with their family crests for special events, so as to have their background identified easily. But during the following Taisho era (1912-1926), moga (modern girls) experimented with “daring” kimono color combinations.

To return to Part 1 of this article, please click here.

For Part 3 of this article, please click here.