TRG Info and Advice

Miso from Scratch

As with many delicious things in the world of Japanese cuisine, it starts with a bean, soybeans to be exact. My miso-making sisters and I were lucky enough to have a friend who had toiled for months to raise organic soybeans (no small feat!), and even luckier that she sold them to us for a song, well, more like an opera. Organic things do cost more, but they are worth it!

This was the fifth (or sixth?) year we had gathered to make miso. Being a Midwestern American, I didn’t grow up eating miso and had certainly never seen my mother or her friends make it. Another sister grew up thinking miso came from a store. The third sister had witnessed her mother making miso, but had never been invited to join in the process. “My mom wanted to do it by herself and wouldn’t let me help, but it looked like fun!” she wistfully recalls.

Most people in Japan still buy miso at the store and few of my generation, or even the generation before, have witnessed it being made. I get the feeling that we are rare, therefore, this small group of sister-friends who rely on each other’s memories to recall the steps and process of this yearly event.

For those of you who have never enjoyed a nourishing bowl of hot miso soup, here is a little background on this “wonderpaste!” Once a luxury dip reserved only for nobles and elite monks, by the Muromachi Period (1392-1573) soybean production had increased enough for farmers to make homemade versions of their own. Its value as a preserved food grew to the point where warlords hired specialists to supply their combat warriors with miso-covered rice balls to carry into battle. People were also known to dry or bake miso, making it easier to bring along.

By the Edo Period (1603-1867), miso soup had been implemented into common people’s everyday lives and this tradition continues today. In response to a population surge in Edo (now Tokyo), miso-making factories started springing up, especially during the Genroku years (1688-1704). This lead to miso being sold in stores, but up until that point, most people just made their own and called it temae miso, which is the humblebrag for “our very own homemade miso.” Not just for soup, modern day miso is used as a condiment or flavor-enhancer in everything from stir-fry to grilled items to ramen broth. Check out this site to learn more about how miso came to be and to see all the ways it can liven up your menu.

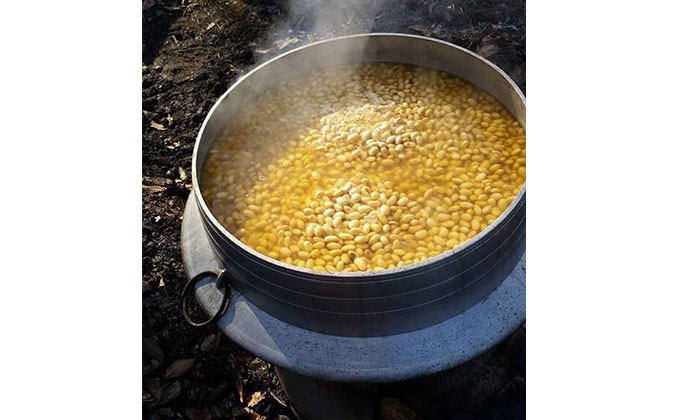

So, we met early one morning in late February to build a fire under a giant cauldron filled to the brim with golden beans. One sister had soaked them the night before and we enlisted the help of our teenage sons to move the immense pot to the kamado, a kind of outdoor Japanese grill. We took turns stoking the fire, skimming off the foam and stirring the beans until they were soft enough to smash. The easy conversation among old friends that stems from performing monotonous tasks side-by-side snaked through various subjects: long-term marriages, unruly children, teenagers and their dreams, learning how to drive a stick-shift in your mid-forties, and bits of the news making its way around the world.

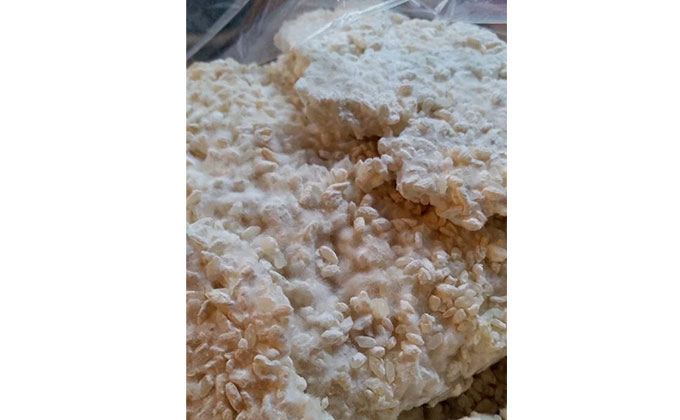

We broke for a quick potluck lunch, then got busy mixing up the rice koji (fermentation culture) with salt. Whitish yellow chunks had to be broken down and mixed with several kilos of salt until the two were thoroughly combined. We did this by hand; pulling, crushing, sifting and rubbing until everything was properly blended. In order to prevent inhaling the miniscule spores of mold, we wore masks, but marveled at how smooth the skin of our hands became.

Side note: It is a common belief among fermenters that your family’s unique enzymes are transferred from your hands to the product, resulting in an umami that is especially suited to you and yours.

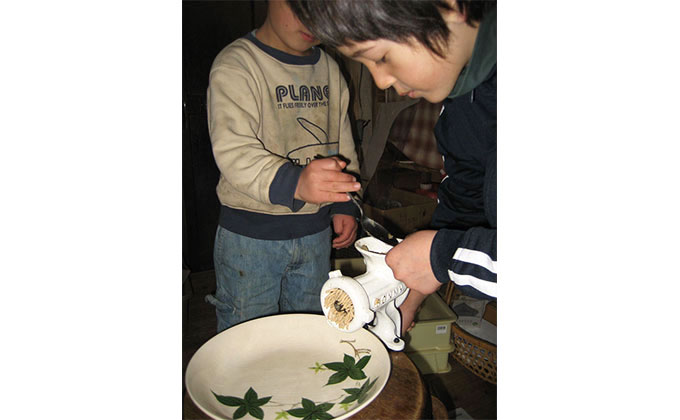

Next came the mashing of the beans. In the past, we had applied various tools to achieve this task, mainly a meat grinder along with mortars and pestles in varying sizes. Two years ago, we stumbled upon the idea of using items normally reserved for making mochi (sticky rice cakes): an usu (a tree-stump-sized wooden mortar) and a kine (giant wooden pestle). With this discovery, we were able to make short work of the vat of softened beans, quickly transforming them into a mashed-potato like consistency which we deposited in the center of the koji-salt mixture like a giant volcano!

Once all of the beans had been pulverized, the task of mixing was upon us again. This time, the volcano of mashed beans was to be combined with the koji and salt. Steam rose from the still-warm mound as we set to work. Hidden pockets of salty culture were coaxed out and joined with the golden mash. Now and again, we added leftover water from the cooked beans to create a smoother texture. We pulled and squished, kneaded and mixed, until finally we had a uniform mixture of the perfect consistency, and hands that had regained their youthful glow.

Next came the task of dividing the future miso into equal parts, so we began forming 500 gram balls. My ten-year-old, gadget-loving son was put in charge of weighing each sphere and adjusting its mass accordingly. After several reports of “Too heavy!” and “Too light!” we figured out the basic size and our production line gained efficiency. Finally, seventy-two 500 gram balls stood at attention and we divided them up between us.

The best and most traditional way to store miso is in a ceramic pot or fermentation vessel. You can also use a large plastic tub with a lid. White liquor is used as a disinfectant around the insides, followed by a thin layer of salt on the bottom. My children have always enjoyed what comes next: throwing the balls with all of your might into the storage container. This is done to remove air pockets which might allow unwanted mold to develop. We worked independently to slam each ball into our respective family pots, then pressed everything down tightly for extra measure. Another thin layer of salt across the top helps keep away pesky, uninvited cultures and I usually top that with bamboo leaves for additional protection.

Happily, we lugged our individual vessels to our vehicles to be taken home and stored in the kura (Japanese storage house), which has thick mud walls that help maintain stable temperatures and levels of humidity. I put weights on top of the bamboo leaves, to press down the beans, aiding in the process of fermentation, but I’ve heard that a collection of small rocks allows for easier adjustment. When a liquid that looks like soy-sauce rises up above the rocks, you simply remove a few of them until the liquid is at a more manageable level. This liquid can also be collected as a gluten-free soy sauce called tamarijouyu, or just tamari. Maybe you have heard of it, used it, or seen it in a store.

Covering the vessel with a thin muslin cloth and securing it with twine before layering on the weights is a method practiced by some miso makers, but I usually don’t. Those without a kura are encouraged to keep the storage container outside in a cool, shady place until summer starts, when it should be moved to a basement or cellar. Making miso in the cooler months of fall will eliminate the storage problem and limit the opportunities for mold growth, but also slow the fermentation process. We usually make miso in late February so that it has time to get nice and steamy during those sauna-like Japanese summers.

Some homemade miso websites recommend stirring the miso once a month, to help prevent the development of molds, but I usually don't touch it unless it starts to stink. A thin layer of white mold across the top is normal and doesn’t affect the miso below, so we just skim it off. Six months is usually long enough for the paste to become delicious miso and develop most of the probiotic goodies that make it so healthy, but I like to leave it for a year if my family can wait. One time, I accidently forgot some miso for about three years! It had turned into the most beautiful dark-red color and tasted like it could cure cancer!

Speaking of which, some types of miso are actually promoted as anti-carcinogens. Other benefits of miso include a variety of vitamins and the presence of a type of bacteria that helps maintain healthy gut flora. As with many fermented foods, the naturally existing anti-nutrients in things like soybeans and grains are reduced in the process of fermentation, making it easier for your body to absorb the good stuff. For more on all the ways eating miso can keep you healthy, check out this article.

Of course, my miso sisters and I were aware of these health benefits to some extent, which is why we were making it in the first place. Plus, it gives us a good excuse to hang out all day, playing with fire and food. This year’s miso-making occurred, ironically, the day after Prime Minister Abe declared that all schools in Japan should close to prevent the spread of the new coronavirus. It gives me peace-of-mind, therefore, to know that this protective, probiotic-rich superfood is a family staple, and will hopefully keep all of those who indulge in its goodness healthy and safe!

photo credits to Fuu Harada and Nariyo Harada